|

| A Woman Under the Influence (Directed by John Cassavetes) |

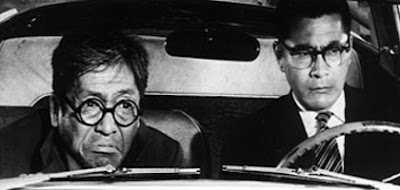

John Cassavetes wrote A Woman Under the Influence (1974) primarily to provide his wife Gena Rowlands with a significant role. Initially envisioned as a trilogy of interconnected plays, the theatrical possibilities seemed intimidating considering Rowland's Mabel character's emotional and physical demands; one single film would suffice. After convincing the American Film Institute to name him filmmaker-in-residence, providing him with access to equipment and facilities, and providing students with on-the-job training— all of which was provided for free — production on one of Cassavetes' most successful films began shortly thereafter.

Nick's (Falk) and, particularly, Mabel Longhetti's chaotic lives is instantly apparent as she scrambles to prepare for a night alone with her husband. For the first of many times, one wonders whether there is a true reason for the mayhem, whether Mabel reacts with self-induced terror, or whether the fear stems from an underlying medical problem. Mabel is the first Cassavetes character to exhibit clinical insanity. Her childish spontaneity and unpredictability contribute to the unease in her relationship with Nick. Meanwhile, as sincere as Nick may be in his own way, he lacks the emotional capacity for genuine care and understanding. Mabel is challenged about her condition and committed, but Nick becomes increasingly deranged, irresponsible, and deadly in the days that follow. When Mabel is not present, a clear co-dependency emerges.

A Woman Under the Influence contains several passages of extraordinary tenderness, complete with genuine companionship, fumbling, and sensitivity. Simultaneously, Nick's incapacity to comprehend Mabel's condition results in explosive aggression and threats of violence. He dominates Mabel by being gruff, impatient, and even brutally honest, while she is brimming with vitality and excitement. Mabel is thus a prototypical Cassavetes character, one who reflects the director's own style of filmmaking. As with Cassavetes' movies, she creates unsettling scenarios, yet as though abandoning the urge for analysis that Cassavetes frequently employed with his films, one of Nick's most egregious errors with Mabel is to rationalise her behaviour. While Cassavetes claims that Mabel's unease is unsurprising, adding, "I don't cast 'totally competent' women in my films because I don't know any 'completely competent' people,"15 Carney also draws connections to his own autobiography. If Moskowitz embodies Cassavetes' swagger, Mabel embodies his self-doubts, uncertainties, and sorrows, he writes.

A Woman Under the Influence concludes with a shaky acclimation process for both the spectator and the protagonists. However, as with Faces and Husbands' unresolved conclusions, the question of whether anything has been accomplished remains. Have Mabel and Nick confronted the underlying nature of their marital and psychological conflicts? Though there is no straightforward resolution, the film's conclusion is satisfying, if only because it establishes a state of respite in which, despite the mayhem, love persists. Cassavetes' work, as Carney puts it, is "stunningly hopeful....[he] never abandoned the promise of possibility." A Woman Under the Influence strikes the ideal balance between Cassavetes' continually erratic style and a more linear causal progression. As an obvious showcase for Rowlands, the picture has a solitary star focus, and it got two Academy Award nominations, for her and for Cassavetes as director, in large part due to her exceptional performance.

“If there’s one quality that separates John Cassavetes’s movies from almost everybody else’s, it’s the density of detail in the storytelling. His films need to be read closely, from beginning to end. There are no lulls with Cassavetes, no lapses in rhythm; the films aren’t broken down the way most are. You have to apprehend them from gesture to gesture, breath to breath. Very few filmmakers in the sound era have chosen to work this way, at least in the realm of fiction. Only Carl Theodor Dreyer, of whom Cassavetes was a great admirer, comes to mind. This is not to slight filmmakers with a different approach to their art, who either break up their scenes in clearly articulated units (Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Bresson), build tableau effects that take the action into an eerie timelessness (Stanley Kubrick), isolate a certain visual or behavioral event as the focal point of a given shot (Jean Renoir), or dig into the marrow of time to make an event out of duration itself (Andy Warhol, Andrei Tarkovsky). Every approach is equally valid, none more elevated than the rest. Die-hard Cassavetes devotees do him no favors when they buy into his own pronouncements and claim that his methods allowed him a greater purchase on the truth (whatever that is) than other filmmakers. “My films are the truth,” he once said during a personal appearance with a filmmaker of my acquaintance; needless to say, my acquaintance was more than a little put off. Yet such pretentiousness is easily forgiven in a man like Cassavetes, just as it’s easy to make allowances for the pomposity contained within Bresson’s book of maxims. When you consider how far against the grain they both went, it’s understandable that they would each accord their own idiosyncratic working methods the status of scientific breakthroughs or archaeological finds.”

– Kent Jones.

In the following extracts John Cassavetes discusses the personal and creative process that led to the writing of his masterpiece A Woman Under the Influence.

I absolutely wrote A Woman Under the Influence to try to write a terrific part for my wife. Gena wanted to do a play. She was always complaining we’re living in California, she loves the theater and everything. Gena really wanted to do a play on Broadway. And I had always fancied that I could write a play. She wanted something big. She said, ‘Now look, deal with it from a woman’s point of view. I mean deal with it so that I have a part in this thing!’ And I said, ‘OK,’ and I went off and had been thinking about it for a year anyway. And I had taken seven or eight tries at bad plays and came up with this play, which was not the play that the movie was, but it was based on the same characters.

And Gena read it and said, no, she wouldn’t do it. And I’m very stubborn so I didn’t realize that she liked the part but that on the stage, to play that every night, would kill her. I had no concept of that because we’re all obsessed, everyone’s obsessed, that is, in this stupid thing. And so I wrote another play on the same subject with the same characters, deepening the characters and making it even more difficult to play. And I gave it to Gena and she said, ‘I like that tremendously. I like the first one too, but I don’t think I could do that on Broadway.’ So I wrote another play, and so now there were three plays! And I took them to New York and I got a producer to produce the plays on Broadway and I thought it was a terrific idea to do these three plays on consecutive nights with matinees, see? [Laughs.] And Gena’s not a particularly ambitious woman in the trade, as it goes. Although, if she sees a good part, she’ll kill herself for it, but I mean kill herself performing it, but not getting it. I mean, it’s either given to her, or she’ll play with the kids or do something else or go out. When Gena read the plays she said, ‘No one could do this every night!’ She feared they would take her to a sanitarium if she became that keyed up over a long period of time! So then I said, well, all right, let’s try to make it a movie.

I can’t just go out and make what I want. I have to go through a whole big process of crap, talking to people and talking to people, proving to them that whatever we are going to do is going to make money. If I can prove it to them that my intentions are to make money, then they will let me make any film I want. But it becomes increasingly more difficult to tell them that since I’m not concerned with making money. You con people and you lie to them. You try to keep a little part of yourself when somebody says to you, ‘You figure it’s the greatest picture ever made?’ You try to keep a little part of yourself alive. So I went through all the processes of calling people in Wisconsin and Idaho and, you know, big industrialists, and trying to find out how to raise the money. And we couldn’t raise anything, not anything!

We had some readings of the play and started to work on the script and got involved in it. I have a definite person in mind when I write, which is why I like to work with people who are very close to me. I know the way they think, so I try – presume, if you will – to put down some of those thoughts, not in their own terms but in the character’s terms. I often get extremely close to someone’s real personal problems, but that’s our hope – no fictitious emotion. Knowing who the two central actors would be, I revised the screenplay. I wrote it for Peter Falk, as he would expect me to. I study his speech patterns and study the way he works, and how he really feels about it, and then start to write off that.

Gena tells everyone that it’s hard to live with me because there is nothing she can say that I don’t write down. I see Gena around the house and with the kids and I tape record what I see. I do tape record things and exaggerate them and blow them up and the incidents are not the same. I mean, I’m not a writer at all! I just record what I hear. As prattle. What people are concerned with in a day’s living. I have a good ear for prattle. Every line in your life is eaten up by the movies you do.

When I first start writing there’s a sense of discovery. In some way it’s not work, it’s finding some romance in the lives of people. You get fascinated with their lives. If they stay with you, then you want to do something – make it into a movie, put it on in some way. It was that which propelled us to keep on working at A Woman Under the Influence. The words kind of spell out the story in a mysterious way. I deal with the characters as any writer would deal with a character. There are certain characters that you like, that you have feeling for, and other characters stand still. So you work until you have all the people in some kind of motion.

Making a film is a mystery. If I knew anything about men and women to begin with, I wouldn’t make it, because it would bore me. I really feel that the script is written by what you can get out of it and how much it means to you. What the film is about is not deliberate in the original intention. I mean, I know that the subject is going to be a family. But I don’t know what my initial motivations are. You’re interested in where you’re going. The idea of taking a laborer and having him married to a wife whom he can’t capture is really exciting. I don’t know how you work on that. So I write – I’ll do it any way I can. I’ll hammer it out; I’ll kick it out; I’ll beat it to death – anyway you can get it. I don’t think there are any rules. The only rules are that you do the best you can. And when you’re not doing the best you can then you don’t like yourself. And that’s very individual with everyone.

The preparations for the scripts I’ve written are really long, hard, intense studies. I don’t just enter into a film and say, ‘That’s the film we’re going to do.’ I think, ‘Why make it?’ For a long time. I think, ‘Well, could the people be themselves, does this really happen to people, do they really dream this, do they think this?’ There were weeks of wrestling to get the script right. I knew hard-hat workers like Nick, and Gena knew women like Mabel, and although I wrote everything myself, we would discuss lines and situations with Peter Falk, to get his opinion, to see if he thought they were really true, really honest. The actors discussed the clothes the characters would be wearing, the influence of money on their lives, the lives of the children, why they sleep on the ground floor, etc. Everything was discussed, nothing came from me alone. We write a lot of things that aren’t in the movie, as background. So that when we got to the scene, you might rewrite on the spot, but we might have already gone in three, four, five, seven, eight, nineteen different versions of the scene.

I do a full and total screenplay and then the actors come to me and tell me what they don’t like. We get together for several weeks, in the evenings, for example, and read the script together. We get on well together, we’ve known each other and worked together for a long time. The actors come up with various suggestions and I ask them to write them down because sometimes I don’t understand what they are trying to say. Gena, for example, read the finished script and said, ‘I hate this woman. What does she do? What clothes does she wear?’ I replied that, at this stage, I didn’t care what she wore. But for her this is important; and she’s right, I had given a superficial response.

I try to get deeper into the characters and find out what the actors want to play. In what they want to play, somehow they’re adding to the film. They’re adding their own sense of reality and perceptions I wouldn’t know from my relatively limited point of view. It’s a necessary part of the process for me. If for me a line is right, I won’t let the actors change it, but will allow them latitude in interpretation.

After Minnie and Moskowitz, I thought, ‘All right, I would like to make a picture to really say something.’ The most important thing in my life, in Gena’s life and in the lives of our intimate friends was the idea of marriage. We were deeply concerned with the change in illusions that marriage engenders over a period of years and the overwhelming need to understand the problems of retaining the family. Out of that came the characters, the feelings for the characters and, in a more specific sense, the complex delineation of the woman in the film.

The film was born out of my despair and questioning of the meaning of my life. As I thought about this, and, later, during the filming, I became very conscious of certain problems that were unknown and foreign to me. I’ll use anything I can to straighten out a problem – even write a movie about it. When I finally saw the finished film, I was shocked by the reality of these problems.

Usually we put film in such simple terms while being endlessly involved in talking about our personal experience. We admit how complex it is. But it’s as though we never look into a mirror and see what we are. So the films I make really are trying to mirror that emotion so we can understand what our impulses are; why we do things that get us into trouble; when to worry about it; when to let them go. And maybe we can find something in ourselves that is worthwhile. Look at it this way: if I were writing a picture and I used a situation which none of us were involved in or interested in, then I’d feel ashamed about doing it – and so would everybody else. So I use absolutely everything I can find in our own lives, in our friends’ lives, to make what we’re doing interesting. But you’d better do it honestly, and you’d better cure all those personal problems that might be holding back something you want to say.

I don’t think audiences are satisfied any longer with just touching the surface of people’s lives; I think they really want to get into a subject.

Love within a family is a universal subject, but one that’s always treated lightly. We’ve learned to gossip about life instead of living it. A woman is either a married housewife who is happy or a married housewife who is unhappy. It’s not that simple. It is possible to be married and in love and unhappy too. And love fluctuates. Marriage, like any partnership, is a rather difficult thing. It has been taken rather lightly in the movies. Family life is so different than what has been fed into us through the tube and through radio and through the casual, inadvertent greed that surrounds us. Films today show only a dream world and have lost touch with the way people really are. For me the Longhetti family is the first real family I’ve ever seen on screen. Idealized screen families generally don’t interest me because they have nothing to say to me about my own life.

I spend months and years working out the philosophical intent of each picture. We create such problems in making a film by being so nuts as to say, ‘What’s underneath these characters? What are we really try- ing to say? Why are most movies so exploitative? Why don’t we go in and try to find out what people are really thinking? Even if we don’t know how to answer the question.’ The idea was to take all the experiences that I’ve had, all the family and love that’s been given, all the bitterness – to take all that and say, ‘OK, we’ve had all this,’ and put it all together.

In replacing narrative, you need an idea. What you do is take an idea that you have about a situation and then translate it into a dramatic situation that seems as normal as everyday life so the audience doesn’t see the idea. So it doesn’t show. Of course the idea itself has to be good – it really has to be first-rate. And the idea in A Woman Under the Influence was a concept of how much you have to pay for love. That’s kind of pretentious, but I was interested in it. And I didn’t know how to do it, and none of the other people knew how either, so we had to work extremely hard. But you have to deal with philosophic points in terms of real things. Children are real. Food is real. A roof over your head is real. Taking the children to the bus is real. Trying to entertain them is real. Trying to find some way to be a good mother, a good wife – I think all those things are real. And they are usually interfered with by the other side of one’s self – which is the personal side, not the profound, wonderful side. And that personal side says, ‘Hey, what about me? Yeah, you can’t do this to me.’ But if you’re in the audience, the audience is saying, ‘Hey, what about me?’ All the way through A Woman Under the Influence the characters are not thinking about themselves – and therefore the audience is allowed to ask that because the characters can’t. In that way, the film was a little unreal. Because in life people stop and say, ‘What about me?’ every three seconds.

I knew that love created at once great moments of beauty and that on the other hand it makes you a prisoner. It just seems to me that women are alone and they are made prisoner by their own love. If they commit to something then they have committed to it and it’s a torture. And it’s true. I mean, I see it in my relationship to Gena. Within such a system men have always been in a more favorable position – they are allowed to test themselves against the rest of the world since they are in contact with it. But I feel it too. A man feels that also. And nobody knows how to handle it. Nobody knows how to handle it.

This is complicated in turn by other characters and their lifestyles that come and go within the structure of the film. The interrelations between the characters must not be made too easy; like people in life, each presents unique problems, so that even though they come from the same class background and share similar experiences, problems still arise. To make sure it wouldn’t be sentimental, when I finished the script I crossed out all the references to love except one.

I think we’re just reporters, all of us basically. We report from a certain editorial point of view on what we feel, on what we see and on what is important to us. A story like this is not newsworthy really – it’s not Watergate, it’s not war; it’s a man and woman relationship, which is always interesting to me.

– Extract from Raymond Carney: Cassavates on Cassavetes.

– Kent Jones.

In the following extracts John Cassavetes discusses the personal and creative process that led to the writing of his masterpiece A Woman Under the Influence.

I absolutely wrote A Woman Under the Influence to try to write a terrific part for my wife. Gena wanted to do a play. She was always complaining we’re living in California, she loves the theater and everything. Gena really wanted to do a play on Broadway. And I had always fancied that I could write a play. She wanted something big. She said, ‘Now look, deal with it from a woman’s point of view. I mean deal with it so that I have a part in this thing!’ And I said, ‘OK,’ and I went off and had been thinking about it for a year anyway. And I had taken seven or eight tries at bad plays and came up with this play, which was not the play that the movie was, but it was based on the same characters.

And Gena read it and said, no, she wouldn’t do it. And I’m very stubborn so I didn’t realize that she liked the part but that on the stage, to play that every night, would kill her. I had no concept of that because we’re all obsessed, everyone’s obsessed, that is, in this stupid thing. And so I wrote another play on the same subject with the same characters, deepening the characters and making it even more difficult to play. And I gave it to Gena and she said, ‘I like that tremendously. I like the first one too, but I don’t think I could do that on Broadway.’ So I wrote another play, and so now there were three plays! And I took them to New York and I got a producer to produce the plays on Broadway and I thought it was a terrific idea to do these three plays on consecutive nights with matinees, see? [Laughs.] And Gena’s not a particularly ambitious woman in the trade, as it goes. Although, if she sees a good part, she’ll kill herself for it, but I mean kill herself performing it, but not getting it. I mean, it’s either given to her, or she’ll play with the kids or do something else or go out. When Gena read the plays she said, ‘No one could do this every night!’ She feared they would take her to a sanitarium if she became that keyed up over a long period of time! So then I said, well, all right, let’s try to make it a movie.

I can’t just go out and make what I want. I have to go through a whole big process of crap, talking to people and talking to people, proving to them that whatever we are going to do is going to make money. If I can prove it to them that my intentions are to make money, then they will let me make any film I want. But it becomes increasingly more difficult to tell them that since I’m not concerned with making money. You con people and you lie to them. You try to keep a little part of yourself when somebody says to you, ‘You figure it’s the greatest picture ever made?’ You try to keep a little part of yourself alive. So I went through all the processes of calling people in Wisconsin and Idaho and, you know, big industrialists, and trying to find out how to raise the money. And we couldn’t raise anything, not anything!

We had some readings of the play and started to work on the script and got involved in it. I have a definite person in mind when I write, which is why I like to work with people who are very close to me. I know the way they think, so I try – presume, if you will – to put down some of those thoughts, not in their own terms but in the character’s terms. I often get extremely close to someone’s real personal problems, but that’s our hope – no fictitious emotion. Knowing who the two central actors would be, I revised the screenplay. I wrote it for Peter Falk, as he would expect me to. I study his speech patterns and study the way he works, and how he really feels about it, and then start to write off that.

Gena tells everyone that it’s hard to live with me because there is nothing she can say that I don’t write down. I see Gena around the house and with the kids and I tape record what I see. I do tape record things and exaggerate them and blow them up and the incidents are not the same. I mean, I’m not a writer at all! I just record what I hear. As prattle. What people are concerned with in a day’s living. I have a good ear for prattle. Every line in your life is eaten up by the movies you do.

When I first start writing there’s a sense of discovery. In some way it’s not work, it’s finding some romance in the lives of people. You get fascinated with their lives. If they stay with you, then you want to do something – make it into a movie, put it on in some way. It was that which propelled us to keep on working at A Woman Under the Influence. The words kind of spell out the story in a mysterious way. I deal with the characters as any writer would deal with a character. There are certain characters that you like, that you have feeling for, and other characters stand still. So you work until you have all the people in some kind of motion.

Making a film is a mystery. If I knew anything about men and women to begin with, I wouldn’t make it, because it would bore me. I really feel that the script is written by what you can get out of it and how much it means to you. What the film is about is not deliberate in the original intention. I mean, I know that the subject is going to be a family. But I don’t know what my initial motivations are. You’re interested in where you’re going. The idea of taking a laborer and having him married to a wife whom he can’t capture is really exciting. I don’t know how you work on that. So I write – I’ll do it any way I can. I’ll hammer it out; I’ll kick it out; I’ll beat it to death – anyway you can get it. I don’t think there are any rules. The only rules are that you do the best you can. And when you’re not doing the best you can then you don’t like yourself. And that’s very individual with everyone.

The preparations for the scripts I’ve written are really long, hard, intense studies. I don’t just enter into a film and say, ‘That’s the film we’re going to do.’ I think, ‘Why make it?’ For a long time. I think, ‘Well, could the people be themselves, does this really happen to people, do they really dream this, do they think this?’ There were weeks of wrestling to get the script right. I knew hard-hat workers like Nick, and Gena knew women like Mabel, and although I wrote everything myself, we would discuss lines and situations with Peter Falk, to get his opinion, to see if he thought they were really true, really honest. The actors discussed the clothes the characters would be wearing, the influence of money on their lives, the lives of the children, why they sleep on the ground floor, etc. Everything was discussed, nothing came from me alone. We write a lot of things that aren’t in the movie, as background. So that when we got to the scene, you might rewrite on the spot, but we might have already gone in three, four, five, seven, eight, nineteen different versions of the scene.

I do a full and total screenplay and then the actors come to me and tell me what they don’t like. We get together for several weeks, in the evenings, for example, and read the script together. We get on well together, we’ve known each other and worked together for a long time. The actors come up with various suggestions and I ask them to write them down because sometimes I don’t understand what they are trying to say. Gena, for example, read the finished script and said, ‘I hate this woman. What does she do? What clothes does she wear?’ I replied that, at this stage, I didn’t care what she wore. But for her this is important; and she’s right, I had given a superficial response.

I try to get deeper into the characters and find out what the actors want to play. In what they want to play, somehow they’re adding to the film. They’re adding their own sense of reality and perceptions I wouldn’t know from my relatively limited point of view. It’s a necessary part of the process for me. If for me a line is right, I won’t let the actors change it, but will allow them latitude in interpretation.

After Minnie and Moskowitz, I thought, ‘All right, I would like to make a picture to really say something.’ The most important thing in my life, in Gena’s life and in the lives of our intimate friends was the idea of marriage. We were deeply concerned with the change in illusions that marriage engenders over a period of years and the overwhelming need to understand the problems of retaining the family. Out of that came the characters, the feelings for the characters and, in a more specific sense, the complex delineation of the woman in the film.

The film was born out of my despair and questioning of the meaning of my life. As I thought about this, and, later, during the filming, I became very conscious of certain problems that were unknown and foreign to me. I’ll use anything I can to straighten out a problem – even write a movie about it. When I finally saw the finished film, I was shocked by the reality of these problems.

Usually we put film in such simple terms while being endlessly involved in talking about our personal experience. We admit how complex it is. But it’s as though we never look into a mirror and see what we are. So the films I make really are trying to mirror that emotion so we can understand what our impulses are; why we do things that get us into trouble; when to worry about it; when to let them go. And maybe we can find something in ourselves that is worthwhile. Look at it this way: if I were writing a picture and I used a situation which none of us were involved in or interested in, then I’d feel ashamed about doing it – and so would everybody else. So I use absolutely everything I can find in our own lives, in our friends’ lives, to make what we’re doing interesting. But you’d better do it honestly, and you’d better cure all those personal problems that might be holding back something you want to say.

I don’t think audiences are satisfied any longer with just touching the surface of people’s lives; I think they really want to get into a subject.

Love within a family is a universal subject, but one that’s always treated lightly. We’ve learned to gossip about life instead of living it. A woman is either a married housewife who is happy or a married housewife who is unhappy. It’s not that simple. It is possible to be married and in love and unhappy too. And love fluctuates. Marriage, like any partnership, is a rather difficult thing. It has been taken rather lightly in the movies. Family life is so different than what has been fed into us through the tube and through radio and through the casual, inadvertent greed that surrounds us. Films today show only a dream world and have lost touch with the way people really are. For me the Longhetti family is the first real family I’ve ever seen on screen. Idealized screen families generally don’t interest me because they have nothing to say to me about my own life.

I spend months and years working out the philosophical intent of each picture. We create such problems in making a film by being so nuts as to say, ‘What’s underneath these characters? What are we really try- ing to say? Why are most movies so exploitative? Why don’t we go in and try to find out what people are really thinking? Even if we don’t know how to answer the question.’ The idea was to take all the experiences that I’ve had, all the family and love that’s been given, all the bitterness – to take all that and say, ‘OK, we’ve had all this,’ and put it all together.

In replacing narrative, you need an idea. What you do is take an idea that you have about a situation and then translate it into a dramatic situation that seems as normal as everyday life so the audience doesn’t see the idea. So it doesn’t show. Of course the idea itself has to be good – it really has to be first-rate. And the idea in A Woman Under the Influence was a concept of how much you have to pay for love. That’s kind of pretentious, but I was interested in it. And I didn’t know how to do it, and none of the other people knew how either, so we had to work extremely hard. But you have to deal with philosophic points in terms of real things. Children are real. Food is real. A roof over your head is real. Taking the children to the bus is real. Trying to entertain them is real. Trying to find some way to be a good mother, a good wife – I think all those things are real. And they are usually interfered with by the other side of one’s self – which is the personal side, not the profound, wonderful side. And that personal side says, ‘Hey, what about me? Yeah, you can’t do this to me.’ But if you’re in the audience, the audience is saying, ‘Hey, what about me?’ All the way through A Woman Under the Influence the characters are not thinking about themselves – and therefore the audience is allowed to ask that because the characters can’t. In that way, the film was a little unreal. Because in life people stop and say, ‘What about me?’ every three seconds.

I knew that love created at once great moments of beauty and that on the other hand it makes you a prisoner. It just seems to me that women are alone and they are made prisoner by their own love. If they commit to something then they have committed to it and it’s a torture. And it’s true. I mean, I see it in my relationship to Gena. Within such a system men have always been in a more favorable position – they are allowed to test themselves against the rest of the world since they are in contact with it. But I feel it too. A man feels that also. And nobody knows how to handle it. Nobody knows how to handle it.

This is complicated in turn by other characters and their lifestyles that come and go within the structure of the film. The interrelations between the characters must not be made too easy; like people in life, each presents unique problems, so that even though they come from the same class background and share similar experiences, problems still arise. To make sure it wouldn’t be sentimental, when I finished the script I crossed out all the references to love except one.

I think we’re just reporters, all of us basically. We report from a certain editorial point of view on what we feel, on what we see and on what is important to us. A story like this is not newsworthy really – it’s not Watergate, it’s not war; it’s a man and woman relationship, which is always interesting to me.

– Extract from Raymond Carney: Cassavates on Cassavetes.