|

| Seven Samurai (Directed by Akira Kurosawa) |

1. Sugata Sanshiro, 1943

Kurosawa’s debut feature, made when he was 33, is set in the late 19th century, and follows a country boy who comes to the city to study martial arts.

‘I remember the first time I said ‘Cut’ – it was as though it was not my own voice at all. From the second time on it was me all right. When I think of this first picture I remember most that I had a good time making it. And at this period it was hard to have a good time making films because it was wartime and you weren’t allowed to say anything worth saying. Back then everyone thought that the real Japanese-style film should be as simple as possible. I disagreed and got away with disagreeing – that much I could say.’

2. Drunken Angel, 1948

The film that brought Kurosawa and Mifune Toshiro together is a thriller about a hoodlum and an alcoholic doctor (his other great actor, Shimura Takashi).

‘In this picture I finally discovered myself. It was my picture: I was doing it and no one else. Part of this was thanks to Mifune. Shimura played the doctor beautifully, but I found that I could not control Mifune. When I saw this, I let him do as he wanted, let him play the part freely. I did not want to smother that vitality. In the end, although the title refers to the doctor, it is Mifune that everyone remembers.

‘His reactions are extraordinarily swift. If I say one thing, he understands ten. He reacts very quickly to the director’s intentions. Most Japanese actors are the opposite of this and so I wanted Mifune to cultivate this gift.

‘One of the reasons for the extreme popularity of this film at the time was that there was no competition – no other films showed an equal interest in people. We had difficulty with one of the characters: that of the doctor himself. Uekusa Jin and I rewrote his part over and over again. Still, he wasn’t interesting. We had almost given up when it occurred to me that he was just too good to be true – he needed a defect, a vice. This is why we made him an alcoholic. At that time most film characters were shining white or blackest black. We made the doctor grey.’

3. Rashomon, 1950

Kurosawa’s masterpiece about a rape and murder as seen from the conflicting perspectives of several characters brought Japanese cinema to the attention of international audiences when it won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951.

‘I think Kyo Machiko was marvellous in the film... so forceful. And it took about a month of work to get that.

‘We were staying in Kyoto, waiting for the set to be finished. While there we ran off some 16mm prints to amuse ourselves. One of them was a Martin Johnson jungle film in which there was a shot of a lion roaming around. I noticed the shot and told Mifune that that was just what I wanted him to be.

‘At the same time Mori [Mori Masayuki, who plays Kyo’s murdered nobleman husband in the film] had seen downtown a jungle picture in which a black leopard was shown. We all went to see it. When the leopard came on Machiko was so upset that she hid her face. I saw and recognised the gesture – it was just what I wanted for the young wife.

‘I like silent pictures and always have. They are often so much more beautiful than sound pictures are. Perhaps they have to be. At any rate, I wanted to restore some of this beauty. I thought of it, I remember, this way: one of the techniques of modern painting is simplification, I must therefore simplify this film.

‘We had our share of troubles in making the picture. After one reel was edited there was a studio fire, and another one during dubbing. I’m not happy when I think back to those times. Also I did not know that the film was being sent to Venice. And it certainly would not have been sent if Giuliana Stramigioli [head of Unitalia Film] had not seen and liked it.’

4. The Idiot, 1951

Kurosawa followed ‘Rashomon’ with an adaptation of Dostoevsky’s novel. His long initial edit was heavily cut by Shochiku, and the film proved a commercial and critical failure.

‘I had wanted to make his film since before Rashomon. Since I was little I’d read Dostoevsky and had thought this book would make a wonderful film. Naturally you cannot compare me to him, but he is still my favourite author – he is the one who writes most honestly about human existence. And I think that when I made this picture I really understood him.’

‘People have said this film is a failure. I don’t think so. At least, as entertainment, I don’t think it is a failure.’

5. Ikiru (Living), 1952

Shimura Takashi gives an unforgettable performance as a bureaucrat who finds meaning in his life after learning he has cancer.

‘What I remember best here is the long wake sequence that ends the film, where from time to time we see scenes in the hero’s later life. Originally I wanted music all under this long section. I talked it over with Hayasaka [Hayasaka Fumio, the great Japanese composer who worked with Kurosawa and Mizoguchi] and we decided on it and he wrote the score.

‘Yet when it came time to dub, no matter how we did it, the scenes and music simply did not fit. So I thought about it for a long time and then took all the music out. I remember how disappointed Hayasaka was. He just sat there, not saying anything, and the rest of the day he tried to be cheerful. I was sorry I had to do it, yet I had to. There is no way now of telling him how I felt – he is gone.

‘He was a fine man. It was as though he (with his glasses) were blind and I was deaf. We worked so well together because one’s weakness was the other’s strength. We had been together ten years and then he died. It was not only my own loss – it was music’s loss as well. You don’t meet a person like that twice in your life.’

6. I Live in Fear, 1955

Kurosawa followed ‘Seven Samurai’ with this sombre film about an ageing man (played by Mifune) haunted by the prospect of nuclear war.

‘While I was making Seven Samurai I went to see Hayasaka, who was sick, and we were talking and he said that if a person was in danger of dying he couldn’t work very well. He was quite ill at the time, very weak, and we did not know when he might die. And he knew this too. Just before this we had had word of the Bikini [atomic] experiments. When he had said a person dying could not work I thought he meant himself – but he didn’t. He meant everyone: all of us.

‘As we [Hashimoto Shinobu, Oguni Hideo and Kurosawa] worked on the script we more and more felt that we were really making the kind of picture with which, after it was all over and the last judgement was upon us, we could stand up and account for our past lives by saying proudly: We made I Live in Fear. And that is the kind of film it turned into.’

7. Throne of Blood, 1957

Shakespeare is translated to 16th-century Japan in Kurosawa’s visually stunning adaptation of ‘Macbeth’.

‘I wanted to make Macbeth. The problem was: how to adapt the story to Japanese thinking. The story is understandable enough, but the Japanese tend to think differently about such things as witches and ghosts. I decided upon the techniques of the Noh, because in Noh style and story are one. I wanted to use the way Noh actors have of moving their bodies, the way they have of walking, and the general composition which the Noh stage provides.’

8. The Bad Sleep Well, 1960

Kurosawa made masterly use of widescreen in this contemporary story, an indictment of corrupt big business.

‘This was the first film of Kurosawa Production, my own unit which I run and finance myself. From this film on, everything was my own responsibility. Consequently I wondered about what kind of film to make. Making a film just to make money did not appeal to me – one should not take advantage of an audience. Instead, I wanted to make a film of some social significance. At last I decided to do something about corruption, because it has always seemed to me that graft, bribery et cetera on a public level is the worst crime that there is. These people hide behind the facade of some great organisation like a company or a corporation – and consequently no one ever really knows how dreadful they are, what awful things they do. Exposing them I thought of as a socially significant act – and so I started the film.

‘But even while we were making it, I knew that it wasn’t working out as I had planned, and this was because I was simply not telling and showing enough.’

9. Yojimbo, 1961

Mifune is at his most iconic here as a samurai who plays two rival factions of a small town off against each other. Sergio Leone famously stole the plot for ‘A Fistful of Dollars’.

‘The story is so ideally interesting that it’s surprising no one else ever thought of it. The idea about rivalry on both sides, and both sides are equally bad. We all know what this is like. Here we are, weakly caught in the middle, and it is impossible to choose between evils. It was truly an enormous popular hit. Everyone at the company said it was because of the sword-fighting. But that is not so – the reason was the character of the hero and what he does. He is a real hero, he has a real reason for fighting. He doesn’t just stand by and wave his sword around.’

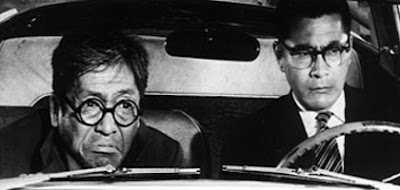

10. High and Low, 1963

Kurosawa adapted Ed McBain’s novel ‘King’s Ransom’ for this riveting, influential thriller about a kidnap.

’Every picture I’ve done has come out of something that has happened to me personally. A friend of mine had a son kidnapped and that kind of barbarism upset me so that I made High and Low. Since then I’ve got lots of letters, people accusing me of teaching people how to go about kidnapping children, but that’s not what I meant. When it happened to him, it happened to me.’

11. Red Beard, 1965

Mifune’s final collaboration with Kurosawa sees him play a doctor in a rural clinic in late-19th century Japan who teaches an arrogant young intern the rewards of caring for the poor. The shoot lasted an exhausting two years.

‘I had something special in mind when I made this film because I wanted to make something… so magnificent that people would just have to see it. To do this we all worked harder than ever, tried to overlook no detail, were willing to undergo any hardship. It was really hard work and I got sick twice.’

12. Kagemusha, 1980

Kurosawa’s first film made in Japan since 1970’s ‘Dodes’ka-den’ was part-funded by 20th Century Fox, following the intervention of George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola.

’I was in America for the Oscar ceremonies when I met George Lucas and Francis Coppola. They approached me and said that they’d learned a lot from my films. Lucas in particular said he would like to assist me in any way he could. At the time, I was trying to negotiate terms for the Kagemusha project with Toho, and we had reached a virtual standstill. Since it was the first time I had met them, I couldn’t tell them that I was lacking money for a project. But someone must have mentioned my problem to them, because they went to 20th Century Fox and persuaded Alan Ladd Jr to invest in the film in return for the rights outside Japan.’

(As told to Tony Rayns, 1981)

13. Ran, 1985

Kurosawa’s visually spectacular epic translated elements of Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’ to 16th-century Japan.

‘What I was trying to get at in Ran – and this was there from the script stage – was that the gods or God or whoever it is observing human events is feeling sadness about how human beings destroy each other, and powerlessness to affect human beings’ behaviour.’

(As told to Michael Sragow, 1986)

– ‘Kurosawa on Kurosawa’. Sight and Sound magazine, July 2010. Original article here.

No comments:

Post a Comment