|

| The Wild Bunch (Directed by Sam Peckinpah) |

The Wild Bunch, directed by Sam Peckinpah, is considered one of the most significant films in the history of American popular culture. It established a new standard for its portrayal of violent action on screen and the director's creative use of multiple cameras, editing, and slow motion, which intensified the visceral impact of the action scenes, was hugely influential. Peckinpah’s intention was to immerse the audience in violence, and attract and repel the audience by bringing to the fore the reality that lay behind the romanticised notion of violence in the traditional Western.

Peckinpah weaves throughout the picture an underlying theme of the western era coming to an end, that these men are out of time, not just their time, but ours as well. The Wild Bunch had a huge effect most noticeably on the Western genre, provocatively moving it into more disturbing territory than it had previously occupied. It further demonstrated to filmmakers the narrative power of irony as an effective tool for exploring and expressing brutality.

Sam Peckinpah had been in the creative wilderness since the commercial and personal failure of Major Dundee, when in late 1967 he was approached by producer Phil Feldman with the script of The Wild Bunch. The screenplay was ultimately credited as having been written by Walon Green and the director himself, developed from a story by Green and Roy N. Sickner.

Walon Green was born and raised in Los Angeles, and attended university in Mexico and Germany. His early film work was as a documentarian for David L. Wolper Productions. He had also worked as a dialogue coach on numerous Hollywood films in the mid-sixties. The Wild Bunch was his first produced screenplay, and was nominated for an Academy Award. The Hellstrom Chronicle, a documentary he produced and filmed in 1971, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary that year. Afterwards, he authored two films for director William Friedkin: Sorcerer starring Roy Scheider, and The Brink's Job which featured Peter Falk. Other scripting credits include Tony Richardson's The Border, which stars Jack Nicholson and was co-written with Deric Washburn and David Freeman, and Stephen Frears' The Hi Lo Country, which stars Woody Harrelson. Walon Green also had considerable success as a writer-producer for television shows such as Hill Street Blues, Law & Order, NYPD Blue, among others.

In the mid 1960s Walon Green, while still a documentary filmmaker, was eager to break into writing features. Green had met Roy Sickner, an aspiring director who had pitched his idea for The Wild Bunch to the producer Reno Carrell, with Sickner himself as director. With the producer's interest Sickner offered Green $1,500 to write a treatment.

From a rough sketch Walon Green wrote a treatment, then the screenplay. When the budget breakdown came in at $4 million, Carrell passed and Sickner shopped it around elsewhere, meeting with some interest but no firm offers. Meanwhile, Green went back to directing documentaries and soon lost track of his script. It eventually found its way to Sam Peckinpah who set about revising it in anticipation for production.

Sickner’s initial idea was to set the story in Mexico in the 1880s, but Green had moved it to Mexico during 1911-13 (which made possible the twin themes of the end of an era and the West in transition that Peckinpah responded to so powerfully). Peckinpah had also admired Green’s elaborate plotting and the complex delineation of relationships between disparate characters and groups.

“The main genesis of the screenplay comes from several things” Green recalled. “I lived in Mexico and worked there for about a year and a half. The Wild Bunch was partly written as my love letter to Mexico”, (interestingly, this was the same reason that Sam Peckinpah gave for wanting to make it).

Green continues: “I had just read Barbara Tuchman's book The Zimmerman Telegram, which is about the Germans' efforts to get the Americans into a war with Mexico to keep them out of Europe. I wanted to allude to some of that, so I gave Mapache German advisors whose commander says that line about how useful it would be if they knew of some Americans who didn't share their government's naive sentiments. I had also seen this amazing documentary, Memorias de Un Mexicano, that was shot while the revolution was actually happening – it's three hours of film taken during the revolution itself. That film had a big influence on the look of The Wild Bunch. I didn't know Sam at this time, but I had Roy see it, and he told me that he made Sam watch it.”

The most obvious historical antecedent for the outlaws themselves is Butch Cassidy’s Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, whom the newspapers nicknamed “the Wild Bunch” and who were chased out of the United States by a posse of Pinkerton detectives.

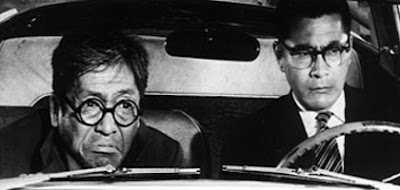

Though writer and director had never met or spoken before production of the film, both men had a shared vision based on their fascination with Mexican culture and history. Another common factor is that they had an admiration for certain filmmakers, most notably John Huston and the Japanese master Akira Kurosawa.

By the time he finished the editing, Walon Green’s tough, gritty screenplay about a band of ruthless outlaws had been transformed by Peckinpah’s vision into a deeply personal, violent epic of elegiac sweep, built on themes of betrayal, revenge, and redemption. The Wild Bunch made Peckinpah’s reputation and still remains to this day a milestone in the history of American cinema, and arguably a masterpiece of the director’s art.

The following is an edited extract from A Conversation with Walon Green, from Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 60s.

I’d like to ask you about a few of Peckinpah’s script changes. Mostly, he sharpened dialogue, but he also made some plot changes. In general, how did Peckinpah’s changes look to you now?

GREEN: Excellent. From beginning to end. It was one of the best examples I’ve ever seen of a writer taking another writer’s script and making it better. After all this time, I could really look at it with a detached eye, and it was quite an experience. The Wild Bunch was the second script I ever wrote and, as I read it through, I thought, ‘‘Boy, if all of them could only be like this!’’ I was also surprised to discover that a number of lines that I always thought I’d written, Sam actually wrote, and vice versa.

How about the flashbacks that Peckinpah added? Especially the ones that show Pike’s abandonment of his best friend, Deke Thornton, and Pike’s ill fated romance with a married woman? Did these events come from the dialogue in the original script, or did Peckinpah originate them?

GREEN: They were only touched on in the dialogue, and when I went to Mexico Sam said, I want some new scenes where this happens and that happens, and I wrote them in a day.

At the very end of the film, Peckinpah decided to let Deke Thornton stay in Mexico with Sykes to help Pancho Villa.

GREEN: Yes, he changed the ending, and I think it was a great idea. Perfect for the film.

Another small but telling addition by Peckinpah was the ants killing the scorpions, which he got from Emilio Fernandez, the Mexican film director who played the role of General Mapache.

GREEN: Yes, and Emilio got it from The Wages of Fear, which opens with a close-up of a small kid torturing cockroaches.

Apparently, Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai also affected your writing of The Wild Bunch and was even responsible for your inclusion of the slow motion violence in the screenplay.

GREEN: Up to that time, The Seven Samurai was the best film that I’d ever seen, and, even today, it’s still in my top ten. I can still remember seeing it for the first time and discussing it endlessly with all my friends, like Jack Nicholson and other people my age. We were all young nobodies back then, and we’d go watch the foreign films, and we’d talk about them all night, and I still remember how the slow motion in the movie just blew us away. So I started thinking, ‘‘Hmm, I wonder what a whole sequence in slow motion would be like? That would really be something!’’ So I told Sickner my idea, and he agreed immediately. He was originally a stuntman, and he thought it could really highlight the key moments of action. So we got all excited about it, and I put it in the script. And one of the first things Sickner told me, when he told me that Peckinpah liked the script, was that Sam wanted to do the action in slow motion…

I wonder if your experience as a documentarian had any affect on the film?

GREEN: Well, except for my love of Mexico and my knowledge of useful historical footage from the Revolution period, I don’t think it had very much effect on the film. I was just getting my documentary career going at the time, but I did see The Wild Bunch as a kind of love letter to Mexico. When I was younger, I went to college in Mexico for a year, and when I finished school, I worked down there for two years for a construction company. I was a site manager on various jobs—building small pumping stations and setting up irrigation projects—and I traveled everywhere, all over the country.

So you knew some of the isolation that the gang felt in the film.

GREEN: I did, but I still loved it down there—the country, the culture, the people, the music, everything. And Sam felt the same way. It was a very strong connection between us.

When you finally saw the film, what was your reaction?

GREEN: I saw it at Warner Bros. in a screening room, and it was very exciting, and I enjoyed it very much. But I saw it with a very rough dub, and I remember complaining about the sound effects. Eventually, I got them to bring in the guy who did the effects on my reptile and insect documentaries.

They redid it?

GREEN: They did. I explained that the sound effects, as they were, were just ‘‘real,’’ and that what we needed was a more impressionistic approach. They had all these amazing visuals, but they were using the same old gun-shot sounds that had been in the Warners library for sixty years.

Peckinpah apparently felt the same way, and he said that he wanted every gunshot to sound different and to be appropriate to the person who was shooting.

GREEN: That’s right.

What did you think of the zooms and the swish pans?

GREEN: It looked all right to me at the time. It was kind of a new look, and it was very interesting to me as a filmmaker. I was amazed that Lucien Ballard, who did True Grit the same year in the old forties Hollywood-style, could make the adjustment so easily. But he did. So I liked all those swish pans and zooms in The Wild Bunch; it made it look, from my point of view, like they were trying to ‘grab’ the story as it happened, and it created a nice feel.

Well, Peckinpah and Ballard didn’t overdo it, like some of the films from that period.

GREEN: Right, and they worked the shots into the context.

How did you feel about the cutting. One critic has claimed that there were 3,642 individual cuts in the film more than any color picture ever made. Some have claimed that it has more cuts than any other picture in film history.

GREEN: I liked it. It didn’t look much different to me from the way I’d originally conceived it. Kurosawa cut a lot. At the beginning of Rashomon, when the woodcutter’s walking through the forest, we see his feet moving along, and his ax, and the trees, and so on. So, yes, it was a stylistic departure from the typical Hollywood film—very much so—but, to my mind, that was the whole idea. There was definitely a whole new sensibility in the air, and The Wild Bunch was part of it.

Were you at the disastrous preview in Kansas City where a number of people walked out, and, supposedly, some actually got sick in the alley outside the theater?

GREEN: No, I wasn’t there, but I certainly heard about it.

Apparently, Warner Bros. didn’t mind the violence, but Peckinpah felt that there was too much, and he cut out six minutes. Later he claimed, ‘‘If I drive people out of the theater, then I’ve failed.’’ What’s your opinion about that controversial aspect of the film? Clearly, both you and Peckinpah intended The Wild Bunch to be an examination of the seduction, even attractiveness of violence, and Stanley Kaufman claimed in The New Republic, ‘‘The violence is the film.’’

GREEN: Absolutely, that was the intention. I don’t know where it came from for Sam, but I know exactly where it came from for me. When I wrote the script, I was hanging around with a bunch of tough guys that I liked very much… their idea of fun was to hit the bars on a Saturday night and start a fight. And sometimes things would get worse, like the time one of the guys robbed an unemployment office and shot two people, and all the other guys went into court and perjured themselves, saying that he was with them all night. I noticed that in all of our conversations, everything always came back to some aspect of violence. If we’re talking about dogs, we’d end up talking about which was the most badass dog there ever was. And if we were talking about people, we’d always end up talking about who was the meanest, toughest guy that ever kicked the shit out of everybody. It was always like that. So I’m sitting there listening to all this, and I’m kind of enjoying myself. I wasn’t doing the bad stuff, per se, although I got in a couple of fights alongside them, which was a necessity. And it started me thinking about this bizarre appeal that violence has for us all—that excites us, that fascinates us, and that runs through all our classical literature. Even in the most controlled of ages, like the Victorian era, there’s always an undercurrent of violence. I can remember Margaret Mead once telling me about the Balinese and pointing out that beneath the soft, rather ephemeral tranquility of their society, there was an extreme of violence, and that all of their legends are about people tearing each other apart and devouring each other, stuff like that. So I was thinking a lot about the disturbing appeal of violence when I got the chance to write The Wild Bunch. And I thought, ‘‘If I can write a movie showing that when these guys start shooting up the town, a young kid will pick up a gun and start shooting back—with a smile on his face—then that’ll get the point across.’’

But that raises a problem because anyone can claim that the violence in his film is just an exploration of human nature?

GREEN: That is a problem, and a danger, but you have to remember that, at the time, no one was making films like The Wild Bunch. It was pre- Clockwork Orange, and the only movies that explored that level of violence on the screen were the Japanese films. In American films, like the Westerns, there was always a ‘‘justified’’ violence. If Indians or outlaws were behaving badly, then they could be shot down with a sense of justice. But I wanted to do a film where it would be very hard to say exactly who’s bad and who’s good in the story. In The Wild Bunch, there are definitely people who are innocent and people who are guilty—the townspeople, for example, are essentially innocent—but who’s really good and who’s really bad? The truth is, most people are generally rounded in such a way that even if you explore the bad people, you’ll sometimes find good in them, and if you examine the good people, you’ll often find bad stuff. Now, of course, there are monsters in this world who are totally evil, but I’m not talking about them, I’m talking in a more general sense…

Now that the dust has settled, The Wild Bunch is considered a landmark, classic Western extolling the virtues of loyalty and obligation, and the film’s even been compared to Sophocles and Camus. What’s your reaction to the film after all these years?

GREEN: I think it’s a terrific film. It was one of those rare times when the chemistry of the script, the directing, the performances, and everything else magically coalesced and created something totally unique. It certainly doesn’t happen very often in this business.

.jpg)