.jpg) |

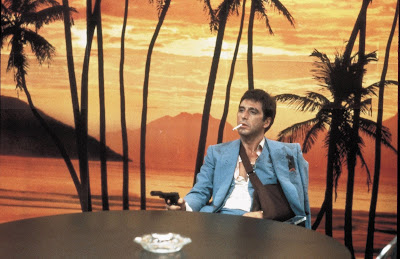

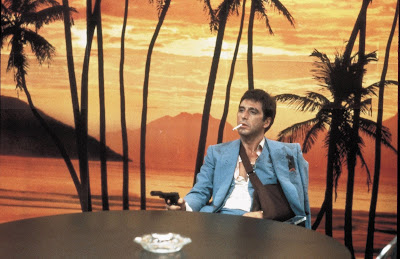

| Scarface (Directed by Brian De Palma) |

In his book Scarface Nation, critic Ken Tucker assesses the lasting cultural impact of Brian De Palma’s 1983 cult hit Scarface – an exuberant blood-drenched spectacle the author calls the ‘ultimate gangster film’ and a work of pop art that has taken on ‘an unruly life of its own’ in the years since its release.

Taking its cue from Howard Hawks’ 1932 original, Tony Montana (Al Pacino) is the titular Scarface, a Cuban immigrant whose violent rise to the top of the southern Florida cocaine industry mixes the outrageous with a stylised realism. For all its trashy excess, the filmmakers root the story in a density of incident and character detail, coupled with a relentless pace that never lets up over its almost three-hours running time. Doomed from the moment he attains power, De Palma emphasises Montana’s alluring yet repellent lifestyle, setting the explicit violence, initially at least, against a backdrop of pastel-pop visuals and bright sunshine.

Dismissed by critics on its release and failing to make much impact at the box office, Tucker recounts how the movie gradually ‘got away from its [middle-aged, white] creators’ and became a hit among ‘largely young, black and Hispanic’ fans.

As the movie shifts visual gear from the opening impressionist sequences to the vivid expressionism of the second half, so Montana’s relentless pursuit of the trappings of wealth leaves him spiritually desolate and isolated. As screenwriter Oliver Stone has stated: ‘Luxury corrupts far more ruthlessly than war,’ a concept he explores in the film’s underlying critique of unbridled materialism and the dark side of the American Dream.

Tucker makes a case for how De Palma’s work redefined the way modern films addressed on-screen violence and drug-use and how its attitude towards women, money and drugs came to be embraced by hip-hop and gangsta rap. As the film captured the attention of urban audiences via home video, it became a focal point for a subculture that was, in the early 1980s, just beginning to emerge. In tracing the cultural fallout of the movie Tucker shows how the makers’ anti-drug and anti-materialist message transitioned in its underground pop-art phase, into a celebration of the criminal life-style by those who identified with Tony Montana’s swaggering consumerism and tragic sense of fighting to the end.

Whatever one thinks of the film’s flaws, or Pacino’s over-the-top performance, a quarter-century after its release, Tucker writes, ‘it remains elusive yet pervasive, the movie that will not go away, but which pops up where you least expect it.’

In the following extract from an interview with the film’s screenwriter Oliver Stone, Stone discusses the background to the writing of Scarface and his thoughts on the film as a cultural phenomenon:

|

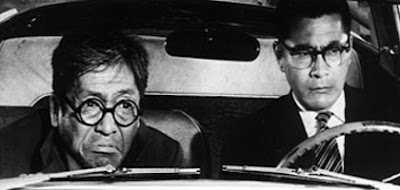

| Scarface (Directed by Howard Hawks) |

The version of Scarface that you wrote was not so much a remake of the original ’30s film but a reinvention in a sense. What was it that appealed to you about remaking the film and having it deal with the drug trade?

The origin of the movie is an interesting story. I had directed

The Hand, and it had failed at the box office. It was completely ignored; in fact, I took a heavy hit. If you go back and check the reviews, there was a lot of personalization in the reviews. It was probably because

Midnight Express really hit people hard, and some people went after me. It was also a period in my life when I needed inspiration; I felt stale as a writer. [Producer] Martin Bregman had approached me, and I said I wasn’t interested in doing it. I didn’t like the original movie that much, it didn’t really hit me at all, and I had no desire to make another Italian gangster picture because so many had been done so well, there would be no point to it. The origin of it, according to Marty Bregman, [is that] Al had seen the ’30s version on television, loved it, and expressed to Marty as his long time mentor/partner that he’d like to do a role like that. So Marty presented it to me; but I had no interest in doing a period piece. Then he called me months later: Sidney Lumet had stepped into the deal. Sidney, who I had met from [my script]

Platoon, was a New York director and he had worked with Al quite a bit. So there was a lot of linkage there. Sidney had a great idea to take the ’30s American prohibition gangster movie and make it into a modern immigrant gangster movie dealing with the same problems we had then – we’re prohibiting drugs instead of alcohol. Prohibition against drugs created the same criminal class as [prohibition of alcohol] created the Mafia. It was a remarkable idea. The Marielitos at the time had gained a lot of publicity for their open brazenness. The Marielitos were the ‘crazies.’ They were deported by Castro in 1981 to America. At the time, it was perceived he was dumping all the criminals into the American system. According to the police enforcement in Miami Beach, they were the poorest people, the roughest people in the prisons, who would kill for a dollar. How could you get this outlandish, operatic character inside an American, contemporary framework? It’s very difficult if you think about it. Al is a brilliant actor. I worked with him on

Born on the Fourth of July in 1978. He was genius in a room. I saw the rehearsal for

Born on the Fourth of July in 1978 with a full cast. He was on fire in that wheelchair. On fire! It stayed with me for ten years. I put as much of that energy as I could into working with Tom [Cruise] in another way.

Did you tailor the role of Tony Montana to Al Pacino?

Of course, from the get-go. It was Al.

Scarface grew out of this Lumet idea of the Marielitos coming to America, the brazenness, the drug trade, making it big, taking over from the old Cuban mob. I went with it and wrote the script. I researched it thoroughly in Florida and the Caribbean. I had been in South America recently and did some research there. So I saw quite a bit of the drug trade from the legal point of view as well as from the gangster point of view. Not many people would talk; it’s a very closed world.

How were you able to get in touch with those people?

I was exposed in certain situations on both sides of the law. I went to the Caribbean – there’s no law down there, they’ll just shoot you in your hotel room. It got hairy; it gave me all this color. I wanted to do a sun-drenched, tropical Third World gangster, cigar, sexy Miami movie. Pacino’s accent was derided at the time [laughs], yet people imitate it to this day. It may not be literally accurate but what the fuck, it works!

I remember you had said in Playboy that at the time you researched the film, you saw a lot of things going on in the drug trade that later played out into big things like Iran Contra.

Oh yeah, the shit was heavy. In Fort Lauderdale, Miami, Miami Beach, Miami Dade, there’s different law enforcement departments, DEA, the FBI, plus Justice, so you have a lot of organizational activity and bureaucracy. And you gotta think about how they interact with each other and how much they all compete. This was the beginning of the drug war. The stories were outlandish. The story of the chainsaw was one of the things that happened that was on the record.

So that was a real incident that happened?

Yes, but not done that way. I dramatized it. They were rough, the Colombians played rough. So I moved to Paris and got out of the cocaine world too, because that was another problem for me. I was doing coke at the time, and I really regretted it. I got into a habit of it, and I was an addictive personality. I did it, not to an extreme or to a place where I was as destructive as some people, but certainly to where I was going stale mentally. I moved out of LA with my wife at the time and moved back to France to try and get into another world and see the world differently. And I wrote the script totally fucking cold sober.

Writing the script, was it in any way a therapy in weaning yourself off the drug?

Oh, it was more than that. One of the things that’s bugged me, and I think a lot of writers will agree with this, is we spend money on our vices and we pay through the nose for our mistakes. I’ll admit that coke kicked my ass. It’s one of the things that beat me in life. As a result, getting even, getting paid to make a movie about it – and making it a good one on top of it – there’s nothing better. But to go back and finish the story as to how the film originated: Sidney Lumet hated my script. I don’t know if he’d say that in public himself; I sound like a petulant screenwriter saying that; I’d rather not say that word. Let me say that Sidney did not understand my script, whereas Bregman wanted to continue in that direction with Al.

Do you feel the story might have been too strong?

Yeah, I think that he felt there was too much gratuitous violence, which was the ultimate rap on the film that came from the critics. From Sidney, it went to a couple of other projections, and then we went to Brian [DePalma], which was a good idea. And Al liked him and trusted him. It turned into a film that has its own history. It basically took off with Brian and Al, and Bregman was the control pilot.

Being that you had a cocaine habit, do you feel it gave your script a different perspective than if you had never tried the drug?

Probably so, because the big switch point for me in the script is the fall of the king. I see Al turning paranoid in that movie, I see it perhaps because I was more attuned to it. But the paranoia of coke is the most striking [aspect], the fire of it. I’ll give you an example. You’re down in the Caribbean, you’re doing coke, you’re drinking at a bar with three Colombian management guys. They run the cigarette boats out there with tons of shit every night. They go right to the Florida coast in these cigarette boats. They fly across the moon, they skim the ocean at night, it’s really incredible, full speed. Then they slow down to nothing, they whisper in the night, and you can’t hear the engines. Then they sneak up past the coast and the by-ways, past the Coast Guard. It’s really a trip. You do this, and you get into that world. All of the sudden, you’re flashing coke in the hotel room at four in the morning; you’re talking the coke talk about how great things are. They started boasting, and I started telling them I was a Hollywood screenwriter. They thought I was an informer because I dropped the name of a guy who had been one of my helpers, who was making money now on the defense side of the ballgame. But the guy had previously busted one of these three guys when he was a prosecutor. So at four in the morning, that gets dangerous! Two of them went into the bath- room and I thought they were gonna come out and blow me away. But you know, the truth of the matter is I got out by bullshit, by the skin of my teeth. I was nervous the whole night, nervous beyond belief. That never could have happened to me if I had been straight. And they never would have taken me to any conference, nor would I have the necessary élan to approach them. I would have been totally out of sorts. You can’t do it from one side of the coin.

[Stone refers to a printed draft of the script for

Scarface.] I enjoyed this very much because it’s one of those scripts like

Wall Street where it’s filled with zingers. We worked on the zingers a lot; they come from the subconscious. What I love about original writing is you can really let out some of your deepest feelings. Sometimes you’re amazed at what comes up. You say stuff that you don’t think as a civilized being you’d say.

So there were some lines of dialogue in the film that reflected your views?

Oh, many of them. That’s the beauty of originals – you can be subversive. Your most subversive side can pop up and you can say anything through a character. You’re not saying it; Tony’s saying it or Manny’s saying it. You can say something so outrageous and if the actor goes along with it, nobody recognizes it as you, and you got away with it in a way.

The restaurant scene where Al Pacino delivers that great monologue is one of my favorites in the film.

‘Say goodnight to the bad guy,’ yeah, yeah, yeah. Where is that? Hold on... [turns pages] Oh yeah, here it is: ‘Is this it? Is this what it’s all about, Manny? Eating-drinking-snorting-fucking, then what? You’re fifty, you got a bag for a belly, you got tits with hair on them, your liver’s got spots and you look like these rich fuckin’ mummies.’ I was in a restaurant in Miami thinking those thoughts [laughs]! Because everyone’s over-fed down there and they live manicured lives. They have Cadillacs, manicured fingers. So I was thinking, man, what could be worse than this kind of death? Luxury is corruption. Corruption lives in luxury. [Continues reading] ‘Is this what I worked for with these hands? Is this what I killed for? For this?’ Well, is this what I killed for is obviously a little over the top, but that’s the direction the script was going. This sounds very Shakespearian: ‘Is this how it ends? And I thought I was a winner.’ How about the one about the women? ‘First you gotta get the power....’

Yeah! That’s one line everybody always talks about, how did you come up with that?

I thought about it: first you gotta get the money in America in my opinion. This was me in 1981–82 when I saw the system in my thirties. First you gotta get the money, then the power, then the chicks. That was the way it works... I think! [laughs]

That sounds like the natural order.

I think in dramatic terms where you hear that kind of concept, it’s power that’s always last, or it’s first, but it’s really the second. It’s funny because the thing that they wanted was not the power but the chicks [laughs]! This one I got from a car dealer, ‘What’s a haza? It’s Yiddish for pig. It’s a guy who’s got more than he needs so he don’t fly straight anymore.’

You got that from a car salesman?

Yeah, not the dialogue but the description of a haza more or less. A guy who wants too much, a pig, a greedy guy. There’s a few in the movie business, I really know ’em! There’s nothing worse than a haza because they pig out. It’s okay to want money and to make it, but when you want too much money then you fuck the other guy. That’s the real drug war in my opinion, in the ’80s anyway. Guys would get to a place and they’d always blow it because they’d want more. Or they were incompetent. They’d go to a place where they had three thousand people working for them and they couldn’t do it any more. They’d go crazy; they’d become paranoid or hit their own supply, or they would become really paranoid. Look at Escobar – the guy went nuts.

What’s interesting about the dialogue in ‘Scarface’ is how often ‘fuck’ is used.

Actually in the script, there’s probably a hundred and something, I think Al made it three hundred and something!

Why was the word used that much?

Because I’d heard it a lot between Vietnam and Miami [laughs]! Also in New York City. It’s not like I grew up in rural town life; I grew up in the heart of the city. If you read the script, the word fuck is used deliberately, it’s not just thrown away. It’s used for rhythm. But Al managed to use it his way by inserting it more and finding the right rhythm. He used it well. I mean with Universal, it was a really tough film, it was really hated at the time.

I remember before ‘Scarface’s release the controversy about the ratings board threatening to give the film an X unless the chainsaw scene was cut down.

Yeah, but it was even more than that. It was the amount of revulsion. I was in LA at the time and the amount of revulsion of so many people inside the industry toward it. Like, ‘This was a horrible thing to do to our industry.’ The critics were so cruel, except a few of them who got it. There was such revulsion, very much like

Natural Born Killers, the bad boy complex, the bad boy movie. It was too much. We had gone one step over. Brian was in the hottest water of all.

When the script was done and the movie was being made, was there any concern from the studio then or did that come after the film was done?

It was a tough movie to make. I think Bregman really championed that one through with Ned Tanen, president of Universal at the time. Ned was his friend and I think Ned was the guy who took the hit. But I’m glad he made the movie. The way they made the movie was torturous for them. It was scheduled to shoot for three months, and it went almost six. I would have shot it another way, but that was Brian’s domain. I learned a lot from Brian. He was very generous; he let me watch everything.

So you were allowed on the set while the movie was being made.

Yeah, at Al’s request too, because dialogue changes were going on all the time.

There’s something interesting I noticed in how Tony has his downfall. Throughout the film he does a lot of bad things, but when he tries to do the right thing and prevents a mother and her children from being killed, that’s what brings about his assassination.

That was intended. It was based in fact on the idea that he was pure in a way. In his honesty there was something pure, and his honesty is such that he cannot kill the innocent child. He just can’t, and it costs him his life.

Let’s talk about the process of writing the film. I remember reading in James Riordan’s biography of you, that your wife at the time, Elizabeth, said you wrote in a very dark room and you shut out the lights of Paris while you were working. Did you feel you needed to be in an environment like that to write the film?

Yeah, I guess so. It’s concentration. It’s basically a womb. I still do it on the movie set because I’m sort of known for building this black cave and carrying it around with me with every shot. But it really is important. It’s not like hubris; I just need separation and concentration. Because what goes on in the movie when you’re directing it is very complicated, there’s a lot of things distracting you, and there’s many levels of thought. But you have to really get the essence of the script. You have to remember what it is you started out to do with the scene, because you’ll get lost otherwise. I think what I do is I reconnect to the origin of the scene. I study the script and I ask, ‘What was it I intended?’ Then I know where I’m going. So I need that womb.

Did you work a specific schedule when you wrote ‘Scarface’? Did you try and write a certain number of pages a day?

No, I’d work forward on a weekly basis. I was not too strict about it, but I would say by the end of the week, I’d like to be here in the process. I believe in going back and getting the first look. The first draft, the first structure is really important. The first draft is formed roughly over six weeks –could be seven or eight, could be three or five, but let’s say six. And doing it in a six-week rough gives you a taste for the movie better. Do it fast, don’t get stuck. Bob Towne probably spent a day fixing a line, but I’m not sure that’s the right solution. I respect him very much as a writer, it’s just a different style of working. With

Midnight Express, I had exactly six weeks, they were pushing me hard. And I did it. The first draft did hold up.

So for ‘Midnight Express’, the movie was pretty much the first draft?

It held up, yeah. On

Scarface, a lot of improvements were made, but I wouldn’t call

Scarface a six-week draft, frankly.

How much longer did you work on revisions after you completed the first draft?

Oh, that was a painful process, because we’re talkin’ Pacino here [laughs]. He was in his heyday when he loved to rehearse. There were a lot of revisions, a lot of revisions of dialog, but the structure didn’t change that much.

You used to work on a typewriter in those days; do you still use one?

No, I’ve moved on. I tried a computer, I’m not wild about the keys. So I use longhand and dictation. I dictate into a machine; I don’t dictate to another person. I’m going over it alone in a room into a machine, and I often retape and retape. I like to speak, I try to act it out. I’ve always done longhand and typing. Now I try to do it through dictation. I think I’m more focused, and you also get into characters. Now that I’ve been around actors a lot of my life, I do some of the acting myself. Sometimes I come up with some crazy stuff. It makes you work a lot harder at externalizing. You can’t fuck around [laughs]. You’re hearing yourself right away. You gotta step up, you’re in the arena. You’re an actor now, you’re no longer a guy hiding in the shadows on the sidelines. It’s an interesting way to work.

.jpg)

You had mentioned earlier how ‘Scarface’ was received very badly when it first came out, but years later it’s really grown in popularity. I hesitate to say it’s a ‘cult’ film, but it’s gained a life of its own.

Oh definitely. We knew that back then. I would hear stories; people would come up to me and say, ‘A bunch of us lawyers we get together to watch

Scarface. We know the lines.’ You’d hear these stories for years. You’d know because people are telling you, and that is the way I judge movies. I have to – look at my career. I mean, I’ve gotten more slams than Bob Evans! There are very radical points of view on me, right? Ultimately, I believe real people who come up to me and tell me in the street. This black dude came up to me the other day, it’s really funny, I thought he was gonna rob me. It was in a parking lot about midnight after a movie. A black dude, about 6’ 2’, strong lookin’ guy comes up to me and circles me as I’m about to get in my car. He says, ‘Hey, are you Oliver Stone?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘You do that football movie?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘Man, that was a really good movie. Man, that said some things, man.’ I was relieved! He appreciated that I did a film about a black quarterback. That was more real for me than a review in the

New York Times, honestly.

Why do you feel ‘Scarface’ became popular years after its release? Do you feel it was ahead of its time?

Scarface was definitely on the money, it was right on. It was exaggerated, but it was close to the truth, but nobody got it at the time.

Miami Vice plunged in right where we [left off]. Michael Mann saw it right away; he told me that. He saw the power of it. They cashed in on it more than we did. They made money on it, we didn’t! I think sometimes the pioneer dies, you know. The pioneer doesn’t make the money. He’s the guy who does it, he dies out, then the next wave is the one that makes it.

For you, what is the relationship between screenwriting and directing?

It’s a process. Screenwriting is really the beginning, the first stage. It’s like giving birth to the fetus. And I think directing is very much civilizing the thing, bringing it on to an adult stage – educating it, clothing it, taming it. Turning it into a civilized human being. And that includes the editing stage as well because I believe directors must work through the editing. They just go hand in hand. I see no conflict at all. It’s just another stage of development, and it makes sense for you to follow through with it.

I need that sense of having seen it on paper. When I wrote those screenplays –

Scarface, Midnight Express – all the directors commented that it was like... Brian De Palma said, ‘It’s like seeing it on paper.’ I make it very clear, sentence by sentence, the direction I’m going. Each sentence outlines a shot. I always wanted to direct the films I was writing. If you love movies it’s like the top position. It’s the one thing you want to do.

Did you write to get the story on paper or were you writing for the reader?

Both. That was the issue, of course. After you get the money, then you go and tilt the screenplay in the revisions. You tilt the screenplay more towards actor, more towards director, and away from the more difficult side of getting the money. Often the earlier drafts would be written with an eye towards the sensational or the, you know, descriptions that deliberately would attract the attention of the financier. That’s the school I’m coming from, the School of Rejection. So, you have to realize the script has got to get made before we can start to get into this business of talking about artistic merit. But the passion was the same.

The passions I expressed were related to personal experiences in my life. When I wrote

Midnight Express, I was very angry with the Turkish system. The theme was injustice. I saw it like a

Les Miserables. Passion governed

Platoon and

Salvador.

Wall Street was very much coming from a desire, again, to make a business movie because my father had worked there. So, I tried to go into that world and write an intelligent movie with Stanley Wiser. Stanley did the first draft, based on my notes. I told him what I wanted and he wrote while I continued editing

Platoon. That was an episode where I was swamped and I needed some help. Stanley hung out with a lot of the people on the Street, turned in a first draft, and we went to work. On that one, we could have benefited from a few extra months. But I rushed it not to get caught up in the... I was just worried about the whole preciousness of this thing. It goes to your head....

I knew I had a lot to learn as a director. I had only done

Platoon and

Salvador and they were war films and there was a great charm to both in some areas. But, I really knew I had to push on and find out other things. In a sense, you could say I became more director than writer at that point, that I became interested in my ability to direct and what I could do as a director. So, my emphasis went there where I had been writing for so many years. I didn’t neglect it, but I didn’t pursue it with the same... it wasn’t the only thing any more. So, I used the advantages of the system, getting other writers to work on material. There’s no reason not to. I don’t have a need to prove I do everything.

– Extract from ‘Oliver Stone Interviewed by Erik Bauer and David Konow’. Creative Screenwriting, Volume 3, #2 (Summer 1996) and Volume 8 #4 (July/August 2001)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)