|

| Three Women (Directed by Robert Altman) |

Three Women directed by Robert Altman is set in a dry, sparsely populated California resort town, where a naive southern lost soul, Pinky Rose (Sissy Spacek), worships and befriends her fellow nurse, the would-be sophisticate Millie Lammoreaux (Shelley Duvall). When Millie takes Pinky in as her flatmate, Pinky’s hero worship gradually evolves into something far stranger and more sinister than either could have expected.

Clearly borrowing its structure from Bergman’s masterly Persona, Altman’s film has typically fine performances from Spacek and Duvall. Often overlooked in Altman’s prestigious oeuvre, it’s now recognised as a a dreamlike triumph that veers from the witty to the frightening and to the surreal, resulting in one of the most remarkable and gripping films of the 1970s.

The following extract is from an interview with the director Robert Altman by Leo Braudy an Robert P. Kolke in front of an audience in Baltimore, Maryland, on March 28, 1981 in which he discusses his inspiration for Three Women, the ending of McCabe and Mrs. Miller and his thoughts on his Raymond Chandler adaptation The Long Goodbye.

AUDIENCE: What kind of preproduction plans do you make?

RA: When we start, when we think about a project and get it to the point where we say we are going to make a film out of this, the first decision I’ll make will be the cinematographer. I’ll set that person or at least do a lot of thinking about it and try to work out what my limitations are, or, in other words, what is out of my control. Then I decide what the visual and audio style of that film is going to be. For instance, in Nashville, or Health, or Brewster McCloud [1970] we were dealing with a real city and real places and we couldn’t control what people wore. We couldn’t say, “All right, nobody in St. Petersburg can wear a red shirt tomorrow.” We have no control, so I know I have to change the style of how that’s going to look, and I have to blend my film in with what is there. A lot of times that will determine the type of cameraman I want to use. In the case of Popeye, Three Women, and Images [1972], where we control, and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, where we create the whole environment, then we can decide how we want this to look to the audience because we do the wardrobe and the construction. Then we start putting our crew together based on what we can’t control and how we are going to do it, and we cast it...

AUDIENCE: Was Three Women based on a dream and how did you cast it? I think it should have won awards.

RA: Thank you. It did, though. Shelley Duvall did win best actress at the Cannes Film Festival for it and the film itself came awful close that year except for three women who were on the jury: [director] Agnes Varda, who felt that the film was dangerous to women and should not be released, [actress] Marthe Keller, and [film critic] Pauline Kael, who loved the first two-thirds of the movie and hated the last third. I tried to point out to her that I don’t make movies in sections, but she just hated the film. But anyway, it did happen from a dream. I dreamed that I was making a film in the desert with Sissy Spacek and Shelley Duvall and that it was called Three Women and it was a character stealing, personality theft kind of thing. I woke up and made some notes on this yellow pad next to my bed and went back to sleep, and then I dreamed some more that I was sending my pro- duction manager out to look for desert locations and I woke up and made more notes on it and went back to sleep. Then I woke up and realized that I don’t keep a yellow pad next to my bed—the whole damn thing was a dream, but it was a dream about making a picture, not of what the picture was, but suggestions came from it. The next day was Sunday. I was depressed at the time. A film had been cancelled that we were going to do, or I chose to step out and cancel it myself. My wife was in the hospital and she was very ill at the time—we didn’t know how seriously. (She is fine now.) I called up the girl who does the casting for me and wardrobe and is probably the top creative associate I have, and I said I read a short story last night and let me tell you what it’s about, and I kind of faked through the thing. I said, do you think it could make a good movie and she said, “Yeah, can you get the rights?” And I said, “Yeah, I think so.” Within nine days of that time I went in to Alan Ladd Jr. That was the first film I did with him and I told him that story. I said I won’t write a script, but I’ll do an outline, and we had the deal for making the picture.

|

| Three Women (Directed by Robert Altman) |

LB: You were talking about actors before and the large creative input that they give to films. In Three Women and Images you were attracted to themes about people turning into other people, robbing personalities. I wonder if actors inspire you that way, the ease with which they go from role to role. Is there something fragile about the actor’s temperament?

RA: I don’t know where that comes from. It is very easy in retrospect for me to see that I make those kinds of pictures. That Cold Day in the Park [1969] was that kind of a picture, Images was that kind of picture, and so was Three Women. They are all very closely akin, what I would call an interior film—where I am dealing with the inside of the person’s head, and what they see or what you see or what I show you that they see may not necessarily be what’s happening. I have some fascination with that. Obviously, I don’t know what it is and I don’t want to know because I keep dealing with that.

RA: I don’t know where that comes from. It is very easy in retrospect for me to see that I make those kinds of pictures. That Cold Day in the Park [1969] was that kind of a picture, Images was that kind of picture, and so was Three Women. They are all very closely akin, what I would call an interior film—where I am dealing with the inside of the person’s head, and what they see or what you see or what I show you that they see may not necessarily be what’s happening. I have some fascination with that. Obviously, I don’t know what it is and I don’t want to know because I keep dealing with that.

|

| McCabe and Mrs. Miller (Directed by Robert Altman) |

LB: When the camera at the end of McCabe and Mrs. Miller goes into Julie Christie’s eye, are we to take that as the film having been seen in some great part from her point of view?

RA: No. I don’t know what that was. I was trying to do the opposite of the normal ending because there is no way to end a film. I mean, life doesn’t stop. The only way I really know to end a film is with the main character’s death. That is the easiest way, so usually you do this big pull back, but I thought why not just go inside of somebody’s head. That little vase that she was using and looking at—we brought that into a studio or garage in order to shoot it, to get as close as we did with that—suddenly it seemed to me when we shot it that it looked like another planet. It’s just the idea that occurs. I’m sure you didn’t see it in Popeye, but if you see Popeye again, you will notice that when Popeye first comes in to the bordello looking for Wimpy and Sweet Pea, we go around that room and in one of those bottom bunks you will see the woman who I call Cinderella, the wash woman, the raggedy woman who is kind of around in the background, who also I think is probably Sweet Pea’s mother. She is lying in that bunk. The preacher is above her smoking an opium pipe and she is look- ing at this same vase, and that’s just fun for me. If it became obvious to an audience, it would be destructive.

RA: No. I don’t know what that was. I was trying to do the opposite of the normal ending because there is no way to end a film. I mean, life doesn’t stop. The only way I really know to end a film is with the main character’s death. That is the easiest way, so usually you do this big pull back, but I thought why not just go inside of somebody’s head. That little vase that she was using and looking at—we brought that into a studio or garage in order to shoot it, to get as close as we did with that—suddenly it seemed to me when we shot it that it looked like another planet. It’s just the idea that occurs. I’m sure you didn’t see it in Popeye, but if you see Popeye again, you will notice that when Popeye first comes in to the bordello looking for Wimpy and Sweet Pea, we go around that room and in one of those bottom bunks you will see the woman who I call Cinderella, the wash woman, the raggedy woman who is kind of around in the background, who also I think is probably Sweet Pea’s mother. She is lying in that bunk. The preacher is above her smoking an opium pipe and she is look- ing at this same vase, and that’s just fun for me. If it became obvious to an audience, it would be destructive.

|

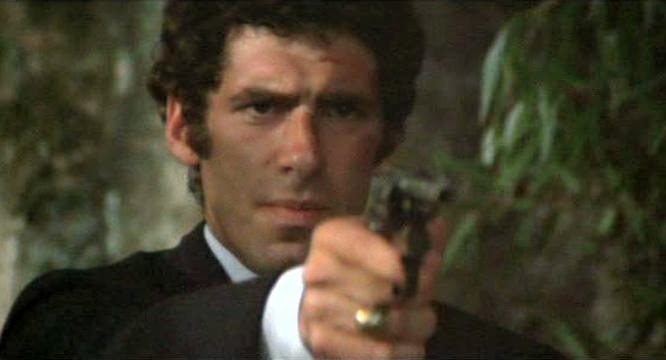

| The Long Goodbye (Directed by Robert Altman) |

AUDIENCE: Was The Long Goodbye [1973] difficult to make?

RA: That was a successful film and should have been much more successful. That film was hurt originally because United Artists wanted to release it as a serious film. They had a poster of Elliot with a cat on his shoulder and a smoking gun and it looked like the ad for The Postman Always Rings Twice [1946]. People went in to see that kind of a film and they were disappointed, and they didn’t like it. We got them to pull the film, and we redid the campaign, opened it several months later in New York, and had that been the original opening, it would have been a very, very successful film. The real dyed-in-the-wool Raymond Chandler fans didn’t like it because, they said, it wasn’t true to the book or to Raymond Chandler, that wasn’t Philip Marlowe. But they weren’t thinking about Raymond Chandler, they were thinking about Humphrey Bogart. I would love to show that film to Raymond Chandler because I think that what I tried to do in The Long Goodbye was the same thing he did in the book. He used those crappy plots that he couldn’t follow himself—I never finished that book either, by the way—but he used them as a device to hang a bunch of thumbnail essays on, observations, and that’s the approach that we took on that picture.

RK: Visually it is your most elaborate film. There is not one shot in that film in which the camera is not moving.

RA: That was another experiment we tried. The camera is constantly moving, but not moving with something, not moving the way it should. You know how you would be in a crowd. You are trying to watch something and it moves and somebody is here and you are just always kind of at the wrong place at the wrong time. That was the kind of tension or attitude I was trying to get in that film. The idea came from a small sequence that we did in Images, where we did the same kind of thing in a short slice, so I felt safe with it, but it seemed to work so well in Images that we thought maybe we could do a whole film that way and The Long Goodbye was the film that followed Images.

– Leo Braudy and Robert P. Kolke. Interview with Robert Altman, In Gerald Duchovnay (ed): Film Voices.

RA: That was a successful film and should have been much more successful. That film was hurt originally because United Artists wanted to release it as a serious film. They had a poster of Elliot with a cat on his shoulder and a smoking gun and it looked like the ad for The Postman Always Rings Twice [1946]. People went in to see that kind of a film and they were disappointed, and they didn’t like it. We got them to pull the film, and we redid the campaign, opened it several months later in New York, and had that been the original opening, it would have been a very, very successful film. The real dyed-in-the-wool Raymond Chandler fans didn’t like it because, they said, it wasn’t true to the book or to Raymond Chandler, that wasn’t Philip Marlowe. But they weren’t thinking about Raymond Chandler, they were thinking about Humphrey Bogart. I would love to show that film to Raymond Chandler because I think that what I tried to do in The Long Goodbye was the same thing he did in the book. He used those crappy plots that he couldn’t follow himself—I never finished that book either, by the way—but he used them as a device to hang a bunch of thumbnail essays on, observations, and that’s the approach that we took on that picture.

RK: Visually it is your most elaborate film. There is not one shot in that film in which the camera is not moving.

RA: That was another experiment we tried. The camera is constantly moving, but not moving with something, not moving the way it should. You know how you would be in a crowd. You are trying to watch something and it moves and somebody is here and you are just always kind of at the wrong place at the wrong time. That was the kind of tension or attitude I was trying to get in that film. The idea came from a small sequence that we did in Images, where we did the same kind of thing in a short slice, so I felt safe with it, but it seemed to work so well in Images that we thought maybe we could do a whole film that way and The Long Goodbye was the film that followed Images.

– Leo Braudy and Robert P. Kolke. Interview with Robert Altman, In Gerald Duchovnay (ed): Film Voices.

_02.jpg)