|

| Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (Directed by Don Siegel) |

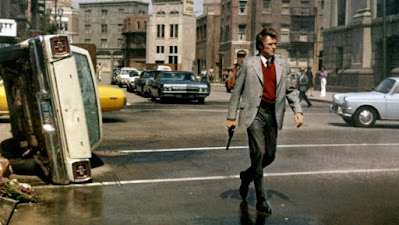

Don Siegel, born 1912 in Chicago, excelled in high-octane action films with tightly woven plots. He regularly collaborated with actor Clint Eastwood, including the classics Coogan’s Bluff (1968) and Dirty Harry (1969).

As a student Don Siegel attended Jesus College, Cambridge, and went to RADA in London to study acting. On returning to America he initially worked as a librarian at Warner Brothers studios in Hollywood. He then worked as an editor before joining the studio’s montage department, where he contributed to a number of films, including Now, Voyager (1942), Casablanca (1942), and Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942).

After working on a couple of uncredited short films he transitioned to feature films. His debut was The Verdict (1946), a police mystery drama that featured the on-screen pairing of Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre for the last time. Night into Night from 1947 starred Ronald Reagan as an epileptic scientist, while Viveca Lindfors portrayed a widow haunted by her late husband; Siegel then directed The Big Steal (1949), a crime caper that featured Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer, and demonstrated Siegel’s aptitude for hard-boiled action, the genre in which he would later establish his reputation.

In 1954, Siegel had his first significant critical and financial success with Riot in Cell Block 11, a classic prison drama. The picture showcased Siegel’s trademark quick pace and crisp editing. Almost as intriguing was Private Hell 36 (1954), a film noir about the complications that ensue when two detectives decide to keep stolen money they retrieve; Ida Lupino starred as a nightclub singer and co-wrote the script.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) was one of the decade’s memorable science fiction films, overcoming a shoestring budget to become a paranoid classic. It is set in a small community that is slowly being overrun by aliens that take over the citizens’ bodies. Widely seen as a rebuke to McCarthyism, the picture functions as both a psychological thriller and a political parable. Despite the studio’s attempt to alter the picture, the finale is nonetheless unsettling: “They’re here already! You’re next!” Despite the fact that Philip Kaufman and Abel Ferrera both produced excellent remakes, this is still the best version.

Crime in the Streets (1956), an adaptation of Reginald Rose’s 1955 television drama, starred John Cassavetes and Mark Rydell as disgruntled adolescents. Siegel’s next film was 1957'’s Baby Face Nelson, a brutal depiction of the famed mobster played by Mickey Rooney.

Siegel achieved more success with The Lineup (1958), a film adaptation of a famous television series. It featured Eli Wallach as a professional assassin tasked with recovering heroin concealed in the luggage of unsuspecting tourists.

Siegel then directed Flaming Star (1960), a Western in which Elvis Presley delivered his best acting performance as a man torn between his white father and his Kiowa mother. Hell Is for Heroes (1962) was a tough World War II film starring Steve McQueen as a rebellious American soldier who eventually leads his exhausted fellow soldiers in an attack against a much larger German army.

Siegel’s attention next shifted to television. He worked on a number of programmes prior to The Killers, a classic crime thriller based on a short novel by Ernest Hemingway about two hit men (Lee Marvin and Clu Gulager) who attempt to learn more about the man they are ordered to kill. Their investigation takes them to a mobster (played by Ronald Reagan in his final feature film) and his lover (Angie Dickinson). Originally intended for television, it was considered too violent for broadcast and instead received a theatrical distribution.

Siegel’s cop films became a standard, from Coogan’s Bluff through to his most renowned feature, Dirty Harry. But probably his most overlooked film is Madigan, a taut, realistic thriller that anticipates both the buddy cop film and Sidney Lumet’s police procedurals. It follows two cops, Madigan (Richard Widmark) and Whitmore (Harry Guardino), as they attempt to track down the killer who stole their guns, while their commissioner (Henry Fonda) struggles with police corruption, brutality, and his own personal life.

Siegel continued his collaboration with Clint Eastwood on Dirty Harry cast in the lead role of the tough, near-fascist cop tasked with apprehending a remorseless killer based on the real-life Zodiac killer. Siegel’s ambivalence with his hero is the film’s most controversial aspect. What is at stake is the extent to which the film is seen to align the viewer unequivocally with Dirty Harry and to present his behaviour as acceptable or even desirable. Eileen McGarry has argued eloquently for the mirroring between hero and villain, even whilst the viewer is encouraged to accept that “the young psychotic killer is portrayed as so exceedingly debased… that he deserves to be slaughtered without consideration” It’s a tense and atmospheric thriller, evocatively using its San Francisco locations and features one of Eastwood's most memorable performances.

Charley Varrick, Siegel's late-period masterwork, is one of the most overlooked crime films of the 1970s. The eponymous character played by Walter Matthau, in one of his most striking and untypical performances, is a crop duster who intends to rob a bank in New Mexico. Varrick's wife and two cops are killed in the process, but things get worse when Varrick and his partner discover that they’ve accidentally ripped off a mob money laundering operation, and they’re being pursued by a group of lurid underworld figures, including Molly (Joe Don Baker) and Boyle (John Vernon). Siegel creates a seedy, desolate world amongst the arid New Mexico landscape, with Baker in particular proving a formidable adversary.

The majority of Siegel’s films exhibit traits that transcend genre standards, such as a pessimistic view of humanity and its social structures. Yet the director’s greatest achievement may have been less in injecting his films with the ‘personality’ of an auteur, than in deftly creating filmic vacuums into which spectator and critics’ views are drawn. As the writer Alan Lovell argues Siegel has “surpassed ordinary professionalism”. The fact that Siegel's best films continue to be both entertaining and a cause of debate long after their release underscores his standing as one of Hollywood’s most intriguing and successful filmmakers.

The renowned director Sam Peckinpah worked as Don Siegel’s assistant director on a number of films. The following account “Don Siegel and Me” is excerpted from the afterword to the 1974 book Don Siegel: Director, by Stuart Kaminsky.

I did six pictures with Mr. Siegel as a dialogue director, and because of this and because of his patience (he couldn’t hire anyone cheaper), I learned.

Brutally honest, he would haul me to the office of a complaining production manager and then find the truth of the matter in question and proceed to chew ass—usually mine. Don has a great anger, a great sense of irony, and a great, warm sense of humor. (I know about the first—I have heard about the latter qualities.) But I must say that usually he was kind enough not to laugh openly while watching me run about with both of my feet in my mouth and my thumb up my ass. (This is not easy.)

In those days (Riot), he was full of anger at every aspect of the production, his personal life, and his associates. But he kept everyone moving with humor and kept us all together and made a superb motion picture (if you freak out on prisons).

I remember the time I was caught sitting down (Private Hell 36) and was told that dialogue directors were a dime a dozen, “and if I wanted to sit on my ass, I could drag it off the set,” and then some time later, he read the pages of a scene I had rewritten; he dragged me to Wanger’s home and fought until I got my first opportunity to work as a screenwriter (a week’s polish on Invasion of the Body Snatchers).

A dedicated, painstaking craftsman, Don was maniacal in his continuing battle against stupid studio authority. He was and is constantly amazed at the idiocy of our industry, while still being delighted by its competence and professionalism. I realized that I might be considered in the latter category when, upon seeing one of my earlier TV shows, he turned away muttering, “You’re not that good!”

When my Quonset hut burnt down in one of the earlier Malibu fires, I sent my kids back to Fresno and moved in with Don and his mother. I was in a complete state of shock. For three weeks, completely flat broke, I was provided with clothing, shelter, and warm understanding. Years later, when a similar tragedy happened to Don, I refused to accept the fact, or even acknowledge that it had even happened, or that it could. I still don’t believe it. He wouldn’t let it—not ever.

If this is beginning to sound like an accolade to a talented filmmaker and close friend, it is and is not. He was my “patron,” and he made me work and made me mad and made me think. Finally, he asked me what his next setup should be on a picture, and for once I was ready, and he used it. I guess that was the beginning.

I was lucky.