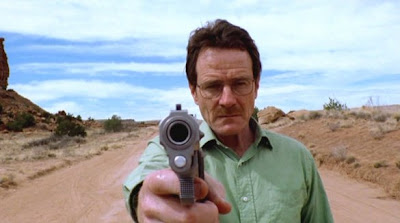

The great AMC drama series Breaking Bad stars Bryan Cranston as Walter White, a high-school chemistry teacher with financial problems. When White discovers he is suffering from terminal cancer he snaps and decides to use his chemistry background to pay for his medical expenses and to take care of his family’s future: he goes into partnership with a former student, played by Aaron Paul, and starts producing and dealing crystal meth.

Breaking Bad premiered in January 2008 and introduced the character of Walter White (Brian Cranston), an otherwise average father who covertly cooks meth to support his family after a cancer diagnosis. Season 1 was shortened due to a writer's strike, however the series resumed in March 2009 for a second season. Once Walt and his associate Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul) entered the drug trade on a full-fledged basis, the stakes increased and the series found its footing.

In its first season, "Breaking Bad" seemed to be a narrative of a midlife crisis run out of control. The concept — felonious father copes with job and family stress— was unmistakably influenced by "The Sopranos," and the clash of ordinary people with colourful and vicious gangsters owes much to the films of the Coen Brothers and Quentin Tarantino. While the narrative and desert backdrop were a reworking of the Western into a more contemporary setting.

It quickly became evident that "Breaking Bad" was a series both rewarding and complex: a ground-breaking reimagining of the serial drama, perhaps only rivalled by The Wire and The Sopranos in its depth of characterisation and moral sweep. What distinguishes the programme from its lesser small screen counterparts is a overwhelming metaphysical dimension. As Walter White nears damnation, Gilligan and his writers raise the stakes in their consideration about good and evil, how it relates to criminality, law, even to modern terrorism. The question is: do we live in a world where criminals go unpunished for their crimes? Or do those who commit evil acts eventually pay the price for their sins?

Gilligan has offered his own personal response to this dilemma. “Breaking Bad” is set in a world where no one gets away with anything and retribution eventually rebounds on evil doers.

Gilligan initially had the concept for Breaking Bad while unemployed and was casually discussing script ideas with a friend. Gilligan imagined a protagonist, a good man, a teacher, gradually morphing into a villain. Walter White’s transition was depicted in the notion of "Mr. Chips becoming Scarface," but he had difficulty pitching the concept to TV networks. Gilligan eventually wrote a framework and pilot to pitch to cable networks, but his proposal was not without its difficulties. The idea was turned down by Showtime who had the similarly themed Weeds on its roster, HBO expressed reservations about a show centreing on a meth dealer, while TNT also declined. Gilligan eventually found an interested buyer in FX — only for them to drop the idea in favour of the Courtney Cox drama Dirt.

Gilligan eventually found a home for Breaking Bad at AMC which was trying to expand its original programming beyond Mad Men. Gilligan eventually won over AMC executives who were intrigued by the concept of Breaking Bad. The project began production and the rest is television history. Since then, Breaking Bad has established an enduring critical reputation as one of the greatest TV series ever made, spawning a spinoff, Better Call Saul, and a companion film, El Camino.

In September 2011 Gilligan was interviewed on the NPR programme Fresh Air by Terry Gross who asked him where the idea for the critically acclaimed show came from, how he came to write convincingly about chemistry and the drug trade, and the direction of the final season.

‘I suspect it had something to do with the fact that when I came up with the idea for Breaking Bad, I was about to turn 40 years old, and perhaps I was thinking in terms of an impending midlife crisis,’ he says. ‘To that end, I think Walter White, in the early seasons, is a man who is suffering from perhaps the world’s worst midlife crisis.’

‘[Because] Walter White was talking to his students, I was able to dumb down certain moments of description and dialogue in the early episodes which held me until we had some help from some honest-to-god chemists,’ says Gilligan. ‘We have a [chemist] named Dr. Donna Nelson at the University of Oklahoma who is very helpful to us and vets our scripts to make sure our chemistry dialogue is accurate and up to date. We also have a chemist with the Drug Enforcement Association based out of Dallas who has just been hugely helpful to us.’

‘My writers and I took a former drug dealer to lunch and picked his brain for a couple of hours,’ says Gilligan. ‘I think he was moving large quantities of marijuana – not methamphetamine – but a lot of the same general philosophies apply to both in the sense of: How do you stay one step ahead of the police? How do you launder large quantities of cash? So things such as that, we seek professional help – just as we do with the chemistry.’

‘There will be 16 more episodes in Season 5. How much darker can Walt get? Is his journey complete – his journey along that arc from good guy to bad guy? At this point, it’s a tricky thing to answer,’ he says. ‘Probably a casual viewer to the show might think [the show is] about morality or amorality. I suppose that there are things that Walt does probably need to atone for – and perhaps he will, when it’s all said and done.’

In an extensive interview in 2010 Vince Gilligan discussed in detail his attitude towards writing and the writing process on Breaking Bad with Kasey Carpenter:

VG: I always like hearing how other writers work. The way we do it is that the breaking of the episode is the hardest part, and the single most important part. We spend the most time on that. It’s very much an all hands on deck scenario. Back on The X-Files, when we did episodes that were stand alone episodes, writers could retreat to their separate offices and brainstorm, take walks, whatever - to figure out their episode. But with a show as serialized as Breaking Bad that just doesn’t work, so what we do is we sit around a big conference table in our very un-fancy offices here in Burbank, and it’s very much like being on a sequestered jury that never ends. Six writers and myself plus our writer’s assistant who, sort of like a court reporter, takes down the notes of what we’re saying on her laptop as we talk so every now and then if we need to pick through the chaff, we can find something good that we would’ve missed if she hadn’t have typed it down. It takes us about two weeks per episode to break it out, five days a week, Monday through Friday, seven to ten hours a day. And the average is pretty consistent, two weeks to break out an episode. We stare at these four three-by-five corkboards that ring the room, we fill one at a time, and when we get to the fifth episode in the cycle, we take number one down from the board and replace it, and so on. Two weeks per corkboard. Each board has: teaser, act one, act two, act three, act four - and brick by brick we build out these episodes, we write out on index cards with sharpies, and each card represents not necessarily a scene, but a beat within a scene so that a teaser will be five or six index cards, and each act will be somewhere between sixteen and eighteen cards, and we try to put as much detail as possible into this portion of the creating of the episode.

KC: If you write better in the beginning, you have less to clean up later.

VG: Exactly. In other words, we try to build the best architectural drawings in the beginning so that any of the writers in the room can go off and write a particular episode by themselves. We cycle through the writers, everyone gets their name on at least two scripts, one by themselves and one shared towards the end of the season. The idea being that it is a group effort. And as I said before, we are asking ourselves those two questions, except we’re asking them over and over again, where is each character’s head at, and what happens next. We can spend a whole day just talking through where Walt’s head is at. He’s done this, he’s done that, and he’s responsible for a plane crash, what is he afraid of, what is he hoping for, what is his goal? And we are trying to think thematically, but we’re employing simple showmanship as well. We want to keep the audience interested, we want to keep the thing moving along like any good cliffhanger/potboiler story. But also, we’re trying to be true to the characters.

KC: What advice do you have for writers?

VG: Well I don’t have any advice that hasn’t been heard a hundred times before, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t good. Writers should write, whether or not you’re getting paid to do it. You’re not a writer unless you’re writing. Then the only differentiation is ‘am I writer who’s making a living off of it, or am I a writer who is currently unsold?’ – and that isn’t a big differentiation. The real differentiation is, are you a writer...?

KC: [laughs] And you can fall in and out of those two pretty easily.

VG: Yes you can, very easily. So that’s not a differentiation worth making. The only one worth making is: are you a writer? Do you write every day? Are you actively involved in creating something, whether you sell it or not. Or are you someone who likes to think about being a writer, but doesn’t actually get much done. That is the only differentiation worth noting. Read as much as possible, view as much as possible. As far as the literary end of things, I don’t have as much experience with novels and short stories, but I can speak to how it is to get a job in the movie and television end of things, although someday I would like to write a book. I don’t know if I’d be any good at it, but that’s always the reason to try something new, to see if you’d be any good at it.

KC: Well it is a lot more solitary than your current situation.

VG: Very true. I like the idea that you can do it anywhere in the world.

KC: And you don’t have to worry about budgetary constraints, CGI, casting, or any of that - it’s just you and the paper, you create your own world and it doesn’t cost you a thing.

VG: That’s true too. I like that. But as far as making it into television or movies, my best advice I give when I’m asked how to get an agent, how to get your stuff read – which is a time-honored question – my answer to that, to speak to how I got started, is to enter screenwriting contests. I was entering these competitions from college on, and I would enter every contest that came down the pike, and once I started writing feature-length things, I would enter these screenplays in every competition I could find. That is how I got my start in the business because of one of those contests, The Governor’s Screenwriting Competition, in my home state of Virginia. I was lucky enough to be one of the winners of it back in 1989, and it was small contest with only thirty or forty entries...

- Extract from ‘Terry Gross: Breaking Bad: Vince Gilligan on Meth And Morals’. NPR article and audio link here

- Extract from ‘Kasey Carpenter: The Voice in Walter White’s Head: An interview with Breaking Bad's creator Vince Gilligan’. Full article here.