|

Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen)

Writers come and go. We always need Indians.

– Producer Ben Geisler in Barton Fink

|

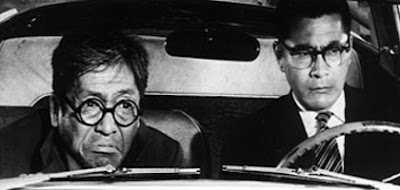

The Coen brothers’ Barton Fink (1991) is the story of a New York writer who aspires to create a new, living theater about the ‘common man’ and who sees it as his job ‘to make a difference.’ The year is 1941, and on the back of the success of his first play, Fink (John Turturro) is lured into a Faustian bargain to go to Hollywood and write for the movies. On arriving in Los Angeles, he forms a friendship with his next-door neighbor and common man Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), and another writer, W. P. Mayhew (John Mahoney), whom Fink considers to be the ‘finest novelist’ of their generation. Fink, however, finds himself unable to make progress on the wrestling picture he’s supposed to be writing. Events turn from bad to bizarre: Mayhew’s secretary and lover, Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis), is revealed to have authored the great writer’s books; in attempting to help Fink, Audrey seduces him only to be later discovered dead in his hotel room; Charlie helps Barton dispose of Audrey’s body; amiable common man Charlie turns out to be a homicidal maniac who possibly murdered Audrey; and Charlie entrusts Barton with a box that may well contain Audrey’s head. In the end, Fink overcomes his writer’s block and is able to finish his wrestling picture, which turns out to echo his New York play. As Fink’s descent into hell is complete, the hotel where he is staying catches fire, and Charlie shoots the detectives who are investigating Audrey’s murder. Barton escapes the blaze as Charlie disappears back into his burning room. In the closing scenes, Barton enters another form of purgatory as the head of the studio refuses to release him from his contract thus retaining the rights to Barton’s writing. Finally, Barton finds himself on a sunny beach and becomes a part of the painting that throughout the movie has hung on the wall of his hotel room.

‘Barton Fink’ takes as its theme the writer’s block suffered by a screenwriter. How did you come to write this kind of film?

JOEL COEN: It did not begin to take shape until we were halfway through the writing of Miller’s Crossing. It’s not really the case that we were suffering from writer’s block, but our working speed had slowed, and we were eager to get a certain distance from Miller’s Crossing. In order to escape from the problems that we were experiencing with that project, we began to think about a project with a different theme. That was Barton Fink, which had two origins. In the first place, we were thinking about putting John Turturro to work – we had known him well for a long time – and so we wanted to invent a character he could play And then there was the idea of a huge abandoned hotel. This idea came even before our decision to set the story in Hollywood.

ETHAN COEN: We wrote the screenplay very quickly, in three weeks, before returning to the script of Miller’s Crossing in order to finish it. This is one of the reasons why these two films were released rather close to one another. When we had finished shooting Miller’s Crossing, we had a script all ready to film.

Why did you set the action in 1941, which was a key era for Hollywood writers? Fitzgerald and Nathanael West had just died, Preston Sturges and John Huston, who had been screenwriters, had just begun careers in directing.

JC: We didn’t know that. In retrospect, we were enthusiastic about the idea that the world outside the hotel was finding itself on the eve of the apocalypse since, for America, 1941 was the beginning of the Second World War. That seemed to us to suit the story. The other reason – which was never truly realized in the film – was that we were thinking of a hotel where the lodgers were old people, the insane, the physically handicapped, because all the others had left for the war. The further the script was developed, the more this theme got left behind, but it had led us, in the beginning, to settle on that period.

EC: Another reason was the main character: a serious dramatist, honest, politically engaged, and rather naive. It seemed natural that he comes from Group Theater and the decade of the thirties.

JC: The character had somewhat the same background, in terms of being a writer, as Clifford Odets; only the resemblance ends there. Both writers wrote the same kind of plays with proletarian heroes, but their personalities were quite different. Odets was much more of an extrovert; in fact he was quite sociable even in Hollywood, and this is not the case with Barton Fink! Odets the man was moreover quite different from Odets the writer. There was a great deal of passion and innocence in him.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

EC: John Turturro was the one who really read it. But you have to take account of the difference between the character and the man.

JC: Turturro was also interested by the style of the Group Theater plays. At the opening of the film, the voice that you hear off camera is that of Turturro, and, at the end, when he taps out a scene from his screenplay on the typewriter, it is meant to be in the Odets style.

The character of W. P. Mayhew is, in turn, directly inspired by Faulkner.

EC: Yes, the southern writer, an alcoholic. Certainly we chose John Mahoney for this role because of his resemblance to Faulkner, but also because we are very eager to work with him. And yet, that was only somewhere to start, and the parallel between the two is pretty superficial. As far as the details of the character are concerned, Mayhew is very different from Faulkner, whose experiences in Hollywood were not the same at all.

JC: Certainly Faulkner showed the same disdain for Hollywood that Mayhew does, but his alcoholism did not incapacitate him, and he continued to be a productive writer.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

EC: What’s ironic about it is that this colonel’s uniform, one of the most surrealist elements in the film, is at the same time one of the few that’s drawn from Hollywood history.

One of the most characteristic qualities of your films and of ‘Barton Fink’ in particular is the fact that their structures are completely unpredictable. Do you put together your screenplays with this in mind?

JC: In this case, we had the shape of the narrative in mind from the very beginning. The structure was freer than usual and we were aware that, toward the middle, the story would take a radical turn. We wanted the beginning of the film to have a certain rhythm and to involve the viewer in a kind of journey. When Fink wakes up and discovers the corpse beside him, we wanted this to be a surprise, and yet not clash with everything that comes before.

EC: We were aware that we would be walking a very thin line here. We needed to surprise the viewer without disconnecting him from the story. In the way we presented the hotel, we hint that Fink’s arrival in Hollywood was not completely ‘normal’. But it is certain that the film is less tied to the conventions of some film genre, as, for example, Miller’s Crossing is, belonging as it does completely to the tradition of the gangster film.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

JC: That came to us pretty soon after we began to ask ourselves what there would be in Barton Fink’s room. Our intention was that the room would have very little decoration, that the walls would be bare and that the windows would offer no view of any particular interest. In fact, we wanted the only opening on the exterior world to be this picture. It seemed important to us to create a feeling of isolation. Our strategy was to establish from the very beginning that the main character was experiencing a sense of dislocation.

EC: The picture of the beach was to give a vision of the feeling of consolation. I do not know exactly why we became fixed on this detail, but it was no doubt a punctuation mark that, in effect, did further the sense of oppression in the room. With the sequence where Fink crushes the mosquito, the film moves from social comedy into the realm of the fantastic.

JC: Some people have suggested that the whole second part of the film is nothing but a nightmare. But it was never our intention to, in any literal sense, depict some bad dream, and yet it is true that we were aiming for a logic of the irrational. We wanted the film’s atmosphere to reflect the psychological state of the protagonist.

EC: It is correct to say that we wanted the spectator to share the interior life of Barton Fink as well as his point of view. But there was no need to go too far. For example, it would have been incongruous for Barton Fink to wake up at the end of the film and for us to suggest thereby that he actually inhabited a reality greater than what is depicted in the film. In any case, it is always artificial to talk about ‘reality’ in regard to a fictional character. It was not our intention to give the impression that he was more ‘real’ than the story itself.

JC: There is another element that comes into play with this scene. No one knows what has killed Audrey Taylor. We did not want to exclude the possibility that it was Barton himself, even though he proclaims his innocence several times. It is one of the conventions of the classic crime film to lay out false trails as long as possible for the viewer. That said, our intention was to keep the ambiguity right to the end of the film. What is suggested, however, is that the crime was committed by Charlie, his next-door neighbor.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

EC: This role too was written for the comedian, and we were quite obviously aware of the warm and friendly image that he projects for the viewer and with which he feels at ease. We played on this expectation by reversing it. Even so, from the moment he appears, there is something menacing, disquieting about this character.

The fact that ‘Barton Fink’ uses working-class characters in his plays obliges him to be friendly to Meadows because if not he would show himself full of prejudice.

JC: That’s true enough in part, but Charlie also wins him over completely by his friendly greeting in the beginning.

EC: Charlie is, of course, equally aware of the role that Barton Fink intends for him to play, if in a somewhat perverse way.

While shooting this film, you weren’t sure if you would go to Cannes, and even less sure that Roman Polanski would be the head of the jury. It is ironic that it was up to him to pass judgment on a film where ‘The Tenant’ and ‘Cul-de-Sac’ meet ‘Repulsion’.

JC: Obviously, we have been influenced by his films, but at this time we were very hesitant to speak to him about it because we did not want to give the impression we were sucking up. The three films you mention are ones we’ve been quite taken by. Barton Fink does not belong to any genre, but it does belong to a series, certainly one that Roman Polanski originated.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

JC: All this is true enough, except that The Shining belongs in a more global sense to the horror film genre. Several other critics have mentioned Kafka, and that surprises me since to tell the truth I have not read him since college when I devoured works like The Metamorphosis. Others

have mentioned The Castle and The Penal Colony, but I’ve never read them.

EC: After the insistence of journalists who wanted us to be inspired by The Castle, I find myself very interested in looking into it.

How did you divide up work on the screenplay?

EC: We handle this in a very informal and simple way We discuss each scene together in detail without ever dividing up the writing on any. I’m the one who then does the typing. As we have said, Barton Fink progressed very quickly as far as the writing was concerned, while Miller’s Crossing was slower and took more time, nearly nine months.

JC: Ordinarily, we spend four months on the first draft, and then show it to our friends, and afterward we devote two further months to the finishing touches.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

EC: Perhaps it was because of the feeling of relief that we got from it in the midst of the difficulties posed by Miller’s Crossing. In any case, it was very easy.

JC: It’s a strange thing but certain films appear almost entirely completed in your head. You know how they will be, visually speaking, and, without knowing exactly how they will end, you have some intuition about the kind of emotion that will be evident at the conclusion. Other scenarios, in contrast, are a little like journeys that develop in stages without your ever truly knowing where they are heading. With this film, we knew as a practical matter where Barton Fink would be at the end.

Moreover, right at the beginning we wrote Charlie’s final speech, the one where he explains himself and says that Barton Fink is only a tourist in that city. It makes things much easier when you know in advance where you’re taking your characters.

EC: We have to say we felt we knew these characters pretty well, maybe because we are very close to the two comedians, which made writing their roles very easy.

Now ‘Miller’s Crossing’ is a film where there are many characters and locations and where several plot lines intersect.

JC: It is true that Barton Fink has a much narrower scope. The narrative of Miller’s Crossing is so complicated because while writing it we had the tendency ourselves to lose our way in the story.

EC: Barton Fink is more the development of a concept than an intertwined story like Miller’s Crossing.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

JC: We knew we came up with it at the very beginning of our work on the screenplay, but we found we couldn’t remember the source. It seems it wound up being what it was by complete chance.

There is a great deal of humor in the film, from the moment when the wallpaper starts peeling off the wall until the pair of policemen arrive on the scene. In fact the combination of drama with comedy is perhaps more evident in ‘Barton Fink’ than in the films that preceded it.

JC: That’s fair enough. The film is really neither a comedy nor a drama. Miller’s Crossing is much more of a drama, and Raising Arizona is much more of a comedy.

EC: It seems that we are pretty much incapable of writing a film that, in one way or another, is not contaminated by comic elements.

JC: That’s funny because at the start I was imagining Miller’s Crossing, while Barton Fink seems to me to be more of a dark comedy.

EC: As opposed to what takes place in regard to Miller’s Crossing, here we tormented the main character in order to create some comic effects.

EC: Except that in Barton Fink the character is mistreated for twenty years. In the end, he gets used to it.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

EC: It’s funny that you should mention that because we actually filmed other shots that would have made for a more conventional transition, but we decided in the end not to use them. All we needed was a rock on the beach that anticipated the film’s end.

This is the second production on which you have worked with your art director, Dennis Gassner.

JC: We shot for at least three weeks in the hotel where half the action of the film takes place. We wanted an art deco stylization and a place that was falling in ruin after having seen better days. It was also necessary that the hotel be organically linked to the film. Our intention, moreover, was that the hotel function as an exteriorization of the character played by John Goodman. The sweat drips off his forehead like the paper peels off the walls. At the end, when Goodman says that he is a prisoner of his own mental state, that this is like some kind of hell, it was necessary for the hotel to have already suggested something infernal.

EC: We used a lot of greens and yellows to suggest an aura of putrefaction.

JC: Ethan always talked about the hotel as a ghost ship floating adrift, where you notice signs of the presence of other passengers, without ever laying eyes on any. The only indication of them is the shoes in the corridor. You can imagine it peopled by failed commercial travelers, with pathetic sex lives, who cry alone in their rooms.

|

| Barton Fink (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

JC: We would have to say yes, probably. But in fact Barton Fink is quite far from our own experience. Our professional life in Hollywood has been especially easy, and this is no doubt extraordinary and unfair. It is in no way a comment about us. We financed Blood Simple, our first film, ourselves, and Circle Films in Washington produced the three next ones. Each time, we made them the offer of a screenplay that they liked and then they agreed on the budget. We have no rejected screenplays in our desk drawers. There are plenty of projects that we started but then didn’t finish writing for one reason or another, either because there were artistic problems we couldn’t resolve or because the cost of producing them would have been prohibitive.

Were any of these aborted projects particularly dear to you?

JC: No, because right away you get drawn into another film, and it becomes your sole preoccupation. We would have liked to produce one or two short subjects that we wrote, but it is very difficult to get them made in America because there’s no market.

Why did you use Roger Deakins on this project?

JC: Our usual director of photography, Barry Sonnenfeld, wasn’t available, and since we had seen Deakins’s work and liked it, we asked him to work with us. He seemed right for the film.

EC: We especially like the night scenes and interior sequences in Stormy Monday. We also screened Sid and Nancy and Pascali’s Island.

Did you make storyboards, as you had for your other films?

EC: Yes, we did detailed ones, but of course there were a lot of changes once we got on the set. However, we went there with a detailed plan for each shot. This was a film much easier to shoot than Miller’s Crossing, and the budget ran about a third less, just like the shooting schedule: eight weeks instead of twelve.

|

| Miller’s Crossing (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

JC: In the case of Miller’s Crossing, there were whole sequences we shot that did not find a place in the film. This was not the case with Barton Fink; we used just about everything. I do remember, however, that we did some shots about life in Hollywood studios, but didn’t decide to keep them; they were too conventional.

Compared to your preceding films, which feature bravura sequences like the night-time shoot-out in ‘Miller’s Crossing’, ‘Barton Fink’ has a much more restrained style.

JC: We weren’t conscious of that. Probably Miller’s Crossing had so many dialogue scenes that at a certain stage we intended to give the spectator some interesting visual effects. The genre also encourages large-scale action scenes. But in the case of Barton Fink this kind of thing did not seem appropriate to us. Stylistic tours-de-force would have ruptured the film’s equilibrium.

The writer victimized by Hollywood is a part of the legend of the cinema.

EC: Right, it’s almost a cliche. Furthermore, we gave the two writers in the film the dignity that victims are accorded, something they maybe didn’t deserve because Barton Fink is probably not a great artist and Mayhew is no longer able to write.

JC: There’s no lack of films that we like, but we don’t see connections between them and our work. The American film industry is doing quite well these days; a number of directors are succeeding in using the screen to express their ideas. In effect, two kinds of films are being produced these days in the United States: the products churned out by the large production companies, which are most often repetitive although there are exceptions, and the films that certain independent directors manage to make.

|

| Miller’s Crossing (Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen) |

JC: At the beginning of Miller’s Crossing, we had two setups: the first was of a drinking glass with ice cubes, then a closeup of Polito. We did not intend to show right away who was holding the glass. You see someone walk off with the glass, you hear the tinkling of the ice cubes, but the character is not visible in the shot. Then you see Polito, you listen to his monologue, and the ice cubes are always part of the scene, but they escape view. Then you see Albert Finney, but you still do not know who is holding the glass, and finally, you get to Gabriel Byrne in the background. All that was set up and laid out in the storyboards.

EC: We intended to create an aura of mystery around the character who was going to become the hero in the film.

JC: Polito is important in this scene because he’s the one who provides the background information as he begins to tell the story.

EC: We held back Gabriel’s entrance into the conversation. He is the last one to talk, five minutes after the beginning of the film.

How do you explain the relative commercial failure of ‘Miller’s Crossing’ despite the good reception it got from critics worldwide?

EC: It is always difficult to speculate about this kind of problem. Perhaps the story is too difficult to follow.

JC: After all the whole plot of The Big Sleep was very difficult to understand! It’s very difficult to analyze failure at the box office, but in any event we were certainly surprised by it.

– ‘Interview with Joel and Ethan Coen’. (From Positif, September 1991). By Michel Ciment and Hubert Niogret. Translation by R. Barton Palmer.