Wednesday, 19 May 2021

Akira Kurosawa: An Interview with “The Emperor of Celluloid”

Saturday, 15 May 2021

On What Makes a Director by Elia Kazan

|

| On the Waterfront (Directed by Elia Kazan) |

In the view of Richard Schickel, Elia Kazan's career, from March 1943 through 1954, was "without a doubt the most astonishing epoch any American director ever experienced." Co-founding the Actors Studio in New York in 1947 and winning two Tony Awards for outstanding theatre director (for Arthur Miller's All My Sons in 1947 and Miller's Death of a Salesman two years later), Kazan increasingly focused his artistic energies on cinema.

Kazan was approached by producer Louis "Bud" Lighton of Twentieth Century Fox who gave Kazan Betty Smith's award-winning novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, launching a five-film deal with the studio. Kazan found various points of personal attachment in this story of Irish immigrants living in early twentieth-century Brooklyn. (Kazan was born to Greek parents in what is now Istanbul, Turkey, and relocated with his family eventually to New York).

In Tess Slesinger and Frank Davis' adaptation of Smith's story, Kazan was drawn to themes linked with immigrant ideals of American potential, “the first piece of material offered me that made me think about my own life and my own dilemma.”

Kazan is hailed as one of the greatest theatre directors-turned-filmmakers of all time while also being roundly rebuked for his infamous testimony against former colleagues and associates during the House Un-American Activities Committee's witch hunts in 1952. Many people have questioned if the voice of an unsettled conscience can be heard in Kazan's films, particularly On the Waterfront (1954).

None, however, have questioned the strength, daring, and subtleties of Kazan's greatest and most enduring films, from A Face in the Crowd (1957)'s still-potent critique of media-made politics to the defiantly sordid vision of debased sexuality in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and Baby Doll (1956). However, Kazan considered the United States to be his greatest and most intimate topic, which he examined with an intense sensitivity to American culture's contrasts.

Indeed, such masterpieces as East of Eden (1955), Splendor in the Grass (1961), Wild River (1960), and America, America (1963) are marked by an insatiable search for the deeper spirit of the American experience.

In the fall of 1973, after a two week retrospective of his films at Wesleyan University, Elia Kazan delivered a timeless speech on directing for film which can now be found in Kazan on Directing.

It should be noted that at the Yale Drama School and elsewhere I had a valuable time as a backstage technician. I was a stage carpenter and I lit shows. Then there was a tedious time as a radio actor, playing hoodlums for bread. I had a particularly educational four years as a stage manager helping and watching directors and learning a great deal. And, in between, I had a lively career as a stage actor in some good plays. All these activities were very valuable to me.

In time, I was fortunate enough to have directed the works of the best dramatists of a couple of the decades which have now become history. I was privileged to serve Williams, Miller, Bill Inge, Archie MacLeish, Sam Behrman, and Bob Anderson and put some of their plays on the stage. I thought of my role with these men as that of a craftsman who tried to realize as well as he could the author’s intentions in the author’s vocabulary and within his range, style, and purpose.

I have not thought of my film work that way.

Some of you may have heard of the auteur theory. That concept is partly a critic’s plaything. Something for them to spat over and use to fill a column. But it has its point, and that point is simply that the director is the true author of the film. The director tells the film, using a vocabulary, the lesser part of which is an arrangement of words.

A screenplay’s worth has to be measured less by its language than by its architecture and how that dramatizes the theme. A screenplay, we directors soon enough learn, is not a piece of writing as much as it is a construction. We learn to feel for the skeleton under the skin of words.

Meyerhold, the great Russian stage director, said that words were the decoration on the skirts of action. He was talking about Theatre, but I’ve always thought his observations applied more aptly to film.

It occurred to me when I was considering what to say here that since you all don’t see directors—it’s unique for Wesleyan to have a filmmaker standing where I am after a showing of work, while you have novelists, historians, poets and writers of various kinds of studies living among you—that it might be fun if I were to try to list for you and for my own sport what a film director needs to know as what personal characteristics and attributes he might advantageously possess.

How must he educate himself?

Of what skills is his craft made?

Of course, I’m talking about a book-length subject. Stay easy, I’m not going to read a book to you tonight. I will merely try to list the fields of knowledge necessary to him, and later those personal qualities he might happily possess, give them to you as one might give chapter headings, section leads, first sentences of paragraphs, without elaboration.

Here we go.

Literature. Of course. All periods, all languages, all forms. Naturally a film director is better equipped if he’s well read. John Ford, who introduced himself with the words, “I make Westerns,” was an extremely well and widely read man.

The Literature of the Theatre. For one thing, so the film director will appreciate the difference from film. He should also study the classic theatre literature for construction, for exposition of theme, for the means of characterization, for dramatic poetry, for the elements of unity, especially that unity created by pointing to climax and then for climax as the essential and final embodiment of the theme.

The Craft of Screen Dramaturgy. Every director, even in those rare instances when he doesn’t work with a writer or two—Fellini works with a squadron—must take responsibility for the screenplay. He has not only to guide rewriting but to eliminate what’s unnecessary, cover faults, appreciate nonverbal possibilities, ensure correct structure, have a sense of screen time, how much will elapse, in what places, for what purposes. Robert Frost’s Tell Everything a Little Faster applies to all expositional parts. In the climaxes, time is unrealistically extended, “stretched,” usually by clasps.

The film director knows that beneath the surface of his screenplay there is a subtext, a calendar of intentions and feelings and inner events. What appears to be happening, he soon learns, is rarely what is happening. This subtext is one of the film director’s most valuable tools. It is what he directs. You will rarely see a veteran director holding a script as he works—or even looking at it. Beginners, yes.

Most directors’ goal today is to write their own scripts. But that is our oldest tradition. Chaplin would hear that Griffith Park had been flooded by a heavy rainfall. Packing his crew, his stand-by actors and his equipment in a few cars, he would rush there, making up the story of the two reel comedy en route, the details on the spot.

The director of films should know comedy as well as drama. Jack Ford used to call most parts “comics.” He meant, I suppose, a way of looking at people without false sentiment, through an objectivity that deflated false heroics and undercut self-favoring and finally revealed a saving humor in the most tense moments. The Human Comedy, another Frenchman called it. The fact that Billy Wilder is always amusing doesn’t make his films less serious.

Quite simply, the screen director must know either by training or by instinct how to feed a joke and how to score with it, how to anticipate and protect laughs. He might well study Chaplin and the other great two reel comedy-makers for what are called sight gags, non-verbal laughs, amusement derived from “business,” stunts and moves, and simply from funny faces and odd bodies. This vulgar foundation—the banana peel and the custard pie—are basic to our craft and part of its health. Wyler and Stevens began by making two reel comedies, and I seem to remember Capra did, too.

American film directors would do well to know our vaudeville traditions.

Just as Fellini adored the clowns, music hall performers, and the circuses of his country and paid them homage again and again in his work, our filmmaker would do well to study magic. I believe some of the wonderful cuts in Citizen Kane came from the fact that Welles was a practicing magician and so understood the drama of sudden unexpected appearances and the startling change. Think, too, of Bergman, how often he uses magicians and sleight of hand.

The director should know opera, its effects and its absurdities, a subject in which Bernardo Bertolucci is schooled. He should know the American musical stage and its tradition, but even more important, the great American musical films. He must not look down on these; we love them for very good reasons.

Our man should know acrobatics, the art of juggling and tumbling, the techniques of the wry comic song. The techniques of the Commedia dell’arte are used, it seems to me, in a film called O Lucky Man! Lindsay Anderson’s master, Bertolt Brecht, adored the Berlin satirical cabaret of his time and adapted their techniques.

Let’s move faster because it’s endless.

Painting and Sculpture; their history, their revolutions and counter revolutions. The painters of the Italian Renaissance used their mistresses as models for the Madonna, so who can blame a film director for using his girlfriend in a leading role—unless she does a bad job.

Many painters have worked in the Theatre. Bakst, Picasso, Aronson and Matisse come to mind. More will. Here, we are still with Disney.

Which brings us to Dance. In my opinion, it’s a considerable asset if the director’s knowledge here is not only theoretical but practical and personal. Dance is an essential part of a screen director’s education. It’s a great advantage for him if he can “move.” It will help him not only to move actors but move the camera. The film director, ideally, should be as able as a choreographer, quite literally. So I don’t mean the tango in Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris or the High School gym dance in American Graffiti as much as I do the battle scenes in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation which are pure choreography and very beautiful. Look at how Ford’s Cavalry charges that way. Or Jim Cagney’s dance of death on the long steps in The Roaring Twenties.

The film director must know music, classic, so called—too much of an umbrella word, that! Let us say of all periods. And as with sculpture and painting, he must know what social situations and currents the music came out of.

Of course he must be particularly into the music of his own day—acid rock; latin rock; blues and jazz; pop; tin pan alley; barbershop; corn; country; Chicago; New Orleans; Nashville. The film director should know the history of stage scenery, its development from background to environment and so to the settings inside which films are played out. Notice I stress inside which as opposed to in front of. The construction of scenery for filmmaking was traditionally the work of architects. The film director must study from life, from newspaper clippings and from his own photographs, dramatic environments and particularly how they affect behavior.

I recommend to every young director that he start his own collection of clippings and photographs and, if he’s able, his own sketches.

The film director must know costuming, its history through all periods, its techniques and what it can be as expression. Again, life is a prime source. We learn to study, as we enter each place, each room, how the people there have chosen to present themselves. “How he comes on,” we say.

Costuming in films is so expressive a means that it is inevitably the basic choice of the director. Visconti is brilliant here. So is Bergman in a more modest vein. The best way to study this again is to notice how people dress as an expression of what they wish to gain from any occasion, what their intention is. Study your husband, study your wife, how their attire is an expression of each day’s mood and hope, their good days, their days of low confidence, their time of stress and how it shows in clothing.

Tuesday, 11 May 2021

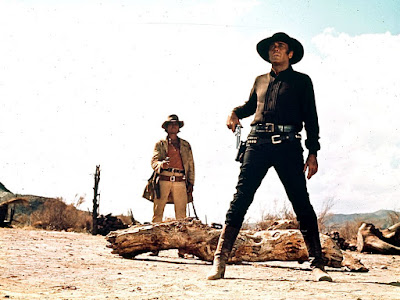

An Interview with Sergio Leone

Sergio Leone came to the fore in the United States with Fistful of Dollars (1964), the first in a series of westerns that established Clint Eastwood as a major film star and gave legitimacy to the “spaghetti western” (a phrase coined by American film critics), a hitherto derided genre. The films that followed, For a Few Dollars More (1965); The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966); Once Upon a Time in the West (1968); Duck You Sucker (a.k.a. Once Upon a Time the Revolution [1971]); and Once Upon a Time in America (1983) all established the distinctive Leone style: the use of quick editing, extreme close-ups, startling transitions, mythic landscapes (usually shot in Almeria, Spain), affected acting, unnatural sound, accompanied by a strong and evocative Ennio Morricone score (frequently composed in advance of the films being shot), heavy-handed humor, and unrestrained violence.

Leone's distinct approach was initially hugely successful in his native Italy and and his first three Westerns were box office smashes across Europe. They were then released in the United States between February 1967 and January 1968, to mixed reviews but impressive box office success. A typical response of the time from critics however, was that European Westerns were "nothing more than cold-blooded attempts at sterile emulation," according to David McGillivray's evaluation in Films and Filming. In English-speaking countries, no major re-evaluation of Leone's work occurred until the 1970s. European films were still mostly neglected in American discussions of the Western genre, Christopher Frayling's 1981 book Spaghetti Westerns had a crucial role in a reassessment of the genre and of Leone in particular.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, filmmakers such as Chabrol, Bertolucci, and Pasolini produced "critical cinema," to which Frayling believes Leone's work belongs. Leone deliberately evokes the themes, characters, and settings of the American Western, distancing these elements from their ideological and historical bases in order to consider aspects of frontier history and mythology that Hollywood studio productions had evaded or ignored, particularly in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Leone's explicit use of reflexive genre clichés in Once Upon a Time in the West, and again in his final film, Once Upon a Time in America, would appear to cast him as a trailblazing post-modernist, but there is a significant difference between Leone's referential system and the ‘blank irony’ identified by Frederic Jameson as central to a post-modern aesthetic.

Leone has a deep emotional and intellectual stake in the cinematic mythology he investigates, no matter how tainted and clichéd they may have become. As a result, as his films become more conscious of the ‘lost' classical American filmic legacy they are leaning on, they begin to take on a pensive, sombre aspect that is utterly absent from the first trilogy's frenetic exuberance. In his book Once Upon a Time in America, Adrian Martin aptly summarised this feature of Leone's latter work:

“It was as if, for Leone, such disembodied ‘quotations’ – if they could be made to retain their mythic intensity and potency – might provide a kind of catharsis or ecstasy for modern-day cinephiles pining over their precious ‘lost object’. That is why, finally, form can never be ‘pure’ in Leone’s work: at stake in it is a psychic investment, a whole elaborate machine of selfhood, culture and longing…”

Leone's films are, in this sense, primarily about interrogating the image of 'America,' without ever really being American in themselves. From a certain perspective, his films make up a small but powerful body of work that may be understood as an extended commemoration, examination, and ultimate sense of loss of the beliefs that underpin twentieth-century American filmmaking. Leone's films have always centred around a concept of America as a ubiquitous cultural presence viewed from a distance. An exciting, violent, intense, and frequently absurd vision.

The following excerpt is from Interview with Sergio Leone, by Pete Hamill. Published in American Film, June 1984.

Question: You seem to be fascinated with American myths, first the myth of the West, now that of the gangster. Why is this?

Leone: I am not fascinated, as you say, by the myth of the West, or by the myth of the gangster. I am not hypnotized, like everyone east of New York and west of Los Angeles, by the mythical notions of America. I’m talking about the individual, and the endless horizon—El Dorado. I believe that cinema, except in some very rare and outstanding cases, has never done much to incorporate these ideas. And if you think about it, America itself has never made much of an effort in that direction either. But there is no doubt that cinema, unlike political democracy, has done what it can. Just consider Easy Rider, Taxi Driver, Scarface, or Rio Bravo. I love the vast spaces of John Ford and the metropolitan claustrophobia of Martin Scorsese, the alternating petals of the American daisy. America speaks like fairies in a fairy tale: “You desire the unconditional, then your wishes are granted. But in a form you will never recognize.” My moviemaking plays games with these parables. I appreciate sociology all right, but I am still enchanted by fables, especially by their dark side. I think, in any case, that my next film won’t be another American fable. But I say that here and I deny it here, too.

Question: Why does the Western seem to be dead as a movie genre? Has the gangster film taken its place?

Leone: The Western isn’t dead, either yesterday or now. It’s really the cinema—alas!—that’s dying. Maybe the gangster movie, in contrast to the Western, enjoys the precarious privilege of not having been consumed to the bones by the professors of sociological truth, by the schoolteachers of demystification ad nauseam. To make good movies, you need a lot of time, a lot of money, and a lot of goodwill. And you need twice as much of it today as you needed yesterday. And the old golden vein, in California’s movieland, where these riches once glistened so close to the surface, unfortunately seems almost completely dried up now. A few courageous miners insist on digging still, whimpering and cursing television, fate, and the era of the spectaculars which impoverished the world’s studios. But they are dinosaurs, delivered to extinction.

Question: What was it that you saw in Clint Eastwood that no one in America had seen at that time?

Leone: The story is told that when Michelangelo was asked what he had seen in the one particular block of marble, which he chose among hundreds of others, he replied that he saw Moses. I would offer the same answer to your question—only backwards. When they ask me what I ever saw in Clint Eastwood, who was playing I don’t know what kind of second-rate role in a Western TV series in 1964, I reply that what I saw, simply, was a block of marble.

Question: How would you compare an actor like Eastwood to someone like Robert De Niro?

Leone: It’s difficult to compare Eastwood and De Niro. The first is a mask of wax. In reality, if you think about it, they don’t even belong to the same profession. Robert De Niro throws himself into this or that role, putting on a personality the way someone else might put on his coat, naturally and with elegance, while Clint Eastwood throws himself into a suit of armor and lowers the visor with a rusty clang. It’s exactly that lowered visor which composes his character. And that creaky clang it makes as it snaps down, dry as a martini in Harry’s Bar in Venice, is also his character. Look at him carefully. Eastwood moves like a sleepwalker between explosions and hails of bullets, and he is always the same—a block of marble. Bobby, first of all, is an actor. Clint, first of all, is a star. Bobby suffers, Clint yawns.

Question: Does it surprise you that an actor could become president of the United States? Should it have been a director?

Leone: I’ll tell you, very frankly, that nothing surprises me any more. It wouldn’t even surprise me to read in the newspapers that a president of the United States, for a change, had become an actor. I wouldn’t be able to hide my surprise if all he did was take on worse films than those done by certain actors who became presidents of the United States. Anyway, I don’t know many presidents, but I do know too many actors. So I know with certainty that actors are like children— trusting, narcissistic, capricious. Therefore, for the sake of symmetry, I imagine presidents, too, are like children. Only a child who became an actor and then a president, for example, could seriously believe that The Day After concealed who knows what new yellow peril.

A director, if possible, would be the least adapted of any to be president. I can picture him more as the head of the Secret Service. He would move the pawns and they would dance, accordingly, to the end, to produce, if nothing else, a good show. If the scene works, great. Otherwise, you redo it. Old Yuri Andropov, if he had been a director instead of a cop, would have enjoyed greater professional satisfaction and— who knows?—he might have lived longer.

Question: Most of your films are very masculine. Do you have anything against women?

Leone: I have nothing against women, and, as a matter of fact, my best friends are women. What could you be thinking? I tolerate minorities. I respect and kiss the hand of the majorities, so you can just about imagine then how I genuflect three or four times before the image of the other half of the heavens. I even, imagine this, married a woman, and, besides having a wretch of a son, I also have two women as daughters. So if women have been neglected in my films, at least up until now, it’s not because I’m misogynist, or chauvinist. That’s not it. The fact is, I’ve always made epic films and the epic, by definition, is a masculine universe.

The character played by Claudia Cardinale in Once Upon a Time in the West seems a decent female character to me. If I can say so, she was a fairly unusual and violent character. At any rate, for a couple of years now. I’ve been harboring the notion of a movie about a woman. Every evening, before going to sleep. I rummage over in my mind a couple of not bad story ideas for it. But either out of prudence or superstition— as is only human, and even too human, I prefer not to talk about it now. I remember that once in 1966 or ’67, I spoke with Warren Beatty about my project for a film on American gangsters and, a few weeks later, he announced that he would produce and star in Bonnie and Clyde. All these coincidences and visions disturb me.

Question: How do you think you fit among the Italian and other European directors? Which directors do you admire? Which are overrated?

Leone: Yes. without a doubt, I, too, occupy a place in cinema history. I come right after the letter L in the director’s repertory, in fact a few entries before my friend Mario Monicelli and right after Alexander Korda, Stanley Kubrick, and Akira Kurosawa, who signed his name to the superb Yojimbo, inspired by an American detective novel, while I was inspired by his film in the making of A Fistful of Dollars. My producer [on that film] wasn’t all that bright. He forgot to pay Kurosawa for the rights, and Kurosawa would certainly have been satisfied with very little and so, afterwards, my producer had to make him rich, paying him millions in penalties. But that’s how the world goes. At any rate, that is my place in cinema history. Down there, between the K’s and the M’s generally to be found somewhere between pages 250 and 320 of any good filmmakers directory. If I’d been named Antelope instead of Leone, I would have been number one. But I prefer Leone; I’m a hunter by nature, not a prey.

To get to the second part of the question, I have a great love for the young American and British directors. I like Fellini and Truffaut. However, I’m not an expert on overrating. You should ask a critic—the only recognized experts on over-, under-, or tepid ratings. The critic is a public servant, and he doesn’t know who he’s working for.

Question: Which comes first: the writer or director?

Leone: The director comes first. Writers should have no illusions about that. But the writer comes second. Directors, too, should have no illusions about that.

Question: What advice would you have for young people who want to be directors?

Leone: I would say, read a lot of comic books, watch TV often, and, above all, make up your minds that cinema is not just something for snobs, other moviemakers, and the mothers of petulant critics. A successful movie communicates with the lowbrow and the highbrow public alike. Otherwise, it’s like a hole without the doughnut around it.

Question: F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “Action is character.” Do you agree?

Leone: The truth is that I am not a director of action, as, in my view, neither was John Ford. I’m more a director of gestures and silences. And an orator of images. However, if you really want it. I’ll declare that I agree with old F. Scott Fitzgerald. I often say myself that action is character. But it’s true that, to be more precise, I say, “Ciack! Action and character, please.” Certainly we must mean the same thing. At other times—for example when I’m at the dinner table—I sometimes say, “Ciack! Let’s eat. Pass the salt.”