|

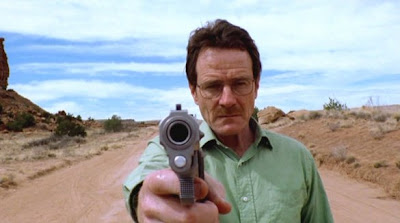

| Peeping Tom (Directed by Michael Powell) |

Obsessiveness and creativity link many of your characters - Anton Walbrook in The Red Shoes and Hoffmann, and Mark Lewis of Peeping Tom.

All artists are more or less obsessed. They’re more interesting when they are - and obsessive.

What led you to make Peeping Tom?

I got in touch with Leo Marks because I’d heard that he’d done a very clever scene involving a cryptogram for Carve Her Name with Pride. It was just after I’d parted from Emeric Pressburger. He first suggested a story of a double agent who betrays both sides but I said I didn’t want to do a spy story. We talked for two or three weeks. Finally, he came to me with this idea, ‘Would you like to make a film about a young man who murders people with his camera?’ I said [clicking his fingers], ‘Yes! You’re on! Just tell me the idea.’ He gave me some ideas and I commissioned him. After that he came round twice a week with more sequences and I would criticise them and he would re-write them. Gradually the script was done that way but he wrote the whole script. It was his idea. Leo Marks.

Was the idea of audience identification with the killer there from the start?

Yes. It’s the way you shoot it. You can look on at a thing or you can preach about it or you can absolutely identify yourself with the young cameraman. Since any good director turns himself into a camera – I Am a Camera is the story of every director - I decided to do it that way. I did the horrifying sequence with the young boy with my son Columba, who was about seven at the time, because I knew he wouldn’t be frightened if he did it with me. Then, as he played my son, I played his father in the film within the film. It gradually grew like that so it became a family affair and the family practically turned into a lens.

Did you anticipate the storm which arose when the film was released?

No. I was very surprised because they weren’t just bad reviews but vicious attacks. They more or less said that I was morbid and diseased in my mind and was trying to influence other people to be the same. I don’t think any director had a worse attack. I was completely taken aback, very surprised, and it did me a lot of harm professionally. It meant that any subject I wanted to do which was unusual - and I have a whole shelf of them - I wasn’t allowed to. I could not raise the money. What I should have done when I realised this was I should have come straight here [to America]. They have not got the prejudices here. I knew my films were known there. I didn’t know they were so admired although I’ve kept friendships here for the forty or fifty years since I started with an American company. But I clung to England because I’m English and naturally wanted to make English films. But I should have seen the writing on the wall and cut and run.

Was Peeping Tom’s voyeurism influenced by Hitchcock?

No, not at all. In Psycho, which I think is his best picture, there’s so much humour inside which saves it. I think he got criticised but they didn’t take it so seriously as they took me.

Don’t you think England has a particularly negative attitude towards creativity, and people doing things in new directions, which is harmful in the end?

I don’t know whether it is a general thing. If they do attack an artist, they’re worse than anybody because a certain amount of hypocrisy comes into it as well. Look at Francis Bacon. He really got severely mauled. But I don’t think the English public and cognoscenti are worse than any others. Perhaps there is a source of hypocrisy which I added to it. Also, being islanders, they really are insular. They’re a bit isolated from continental thought and I never have been. I’ve always been very closely identified with everything that’s happening there. I know a lot about it, a lot about art, and they may be a little bit jealous.

I’ve read that you originally wanted Pamela Brown to play Anna Massey’s other instead of Maxine Audley.

Yes, because she and Anna Massey could easily be mother and daughter. They look a bit like each other and have almost the same colour hair. Pamela’s was a deep red. Anna’s was more chestnut. They would have made a wonderful mother and daughter.

Mark’s stepmother is blonde. So are the prostitutes he kills. Was he taking something against his stepmother out of them?

Well, I didn’t go that deeply into it except instinctively.

I have read somewhere that you have stated your admiration for Walt Disney.

He was one of the great innovators in film. One of the things I like was - when talkies came in, a lot of the timing of silent films went out of the window and nobody made those marvellous slapstick comedies any more because there were only verbal jokes. But Disney kept on making those wonderful cartoons for at least another ten years so he kept the whole idea of film comedy and narrative through image alive. People don’t realise that they owe an enormous lot to him. His films still move. For five years they just bogged down in a welter of talk. He was a great inventor and innovator. I was very fond of him. Whenever I was in Hollywood after the war, I always spent a day with him.

There are surrealistic and fantasy elements in all of your films, particularly The Small Back Room. Which branch of surrealism interests you?

I don’t altogether agree about surrealism because, trained as I have been from the very early days, films are surrealistic. Any film. Because anybody who can start to tell a story in a street or a field just using a camera and an actor - that’s pure surrealism. Anything may happen. It’s more expressionism that you are referring to. This was a sequence where David Farrar was waiting for the girl to come back to the room. There’s a wonderful shot of him underneath, the bottle falling over on him. We made several bottles of different sizes and shot them from different angles and had great fun doing it. But the critics jumped on me immediately, ‘Oh, Michael Powell with his German tendencies and German art director must have these German expressionist ideas!’

There are somethings which have worked very well like those giant pencils in Mark’s pocket in Peeping Tom.

They were about three-and-a-half feet long. That’s the only way you could have done that. Leo wrote the sequence just like that - the pencils fall out of his pocket. I said, ‘You realise, Leo, they’re only that big. The gantry of a studio is forty feet up. I can do it all right.’ When he saw it, he said that it was one of the best shots in the picture but he never knew at the time. I asked the prop man to give me some dummy pencils and pens to drop in this sequence, three feet long! And it worked.

- Michael Powell interviewed by Tony Williams. Films and Filming: Nov 1981